FLASHBACK 137: Memories, circa 1963-66

TweetIF you've been wondering where I've been, truth is with COVID-19, there's just been a lot of tail-chasing stories which I've happily left to others while being prompted to write a memoir, as inspired by former journo colleagues Derek Pedley and Vincent Ross.

Derek is deeply into his memoir and Vince has written a rich book about Aussie diggers and the Kokoda Trail. They got me thinking and suddenly the first line of what you may (or may NOT) be about to read popped into my head.

It qualifies as a "Flashback" though it is maybe a little more. So here is Part One of Chapter One in my life of five decades in basketball ...

IT was the most difficult question I’d ever been asked. But then, in fairness, I was only seven.

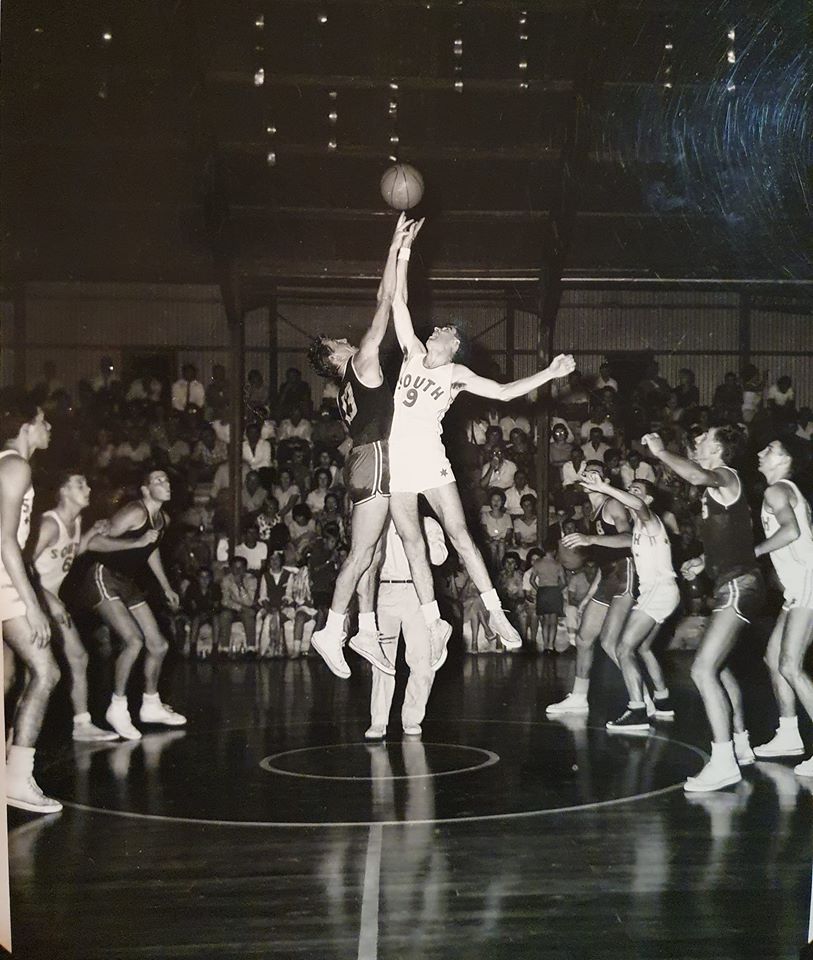

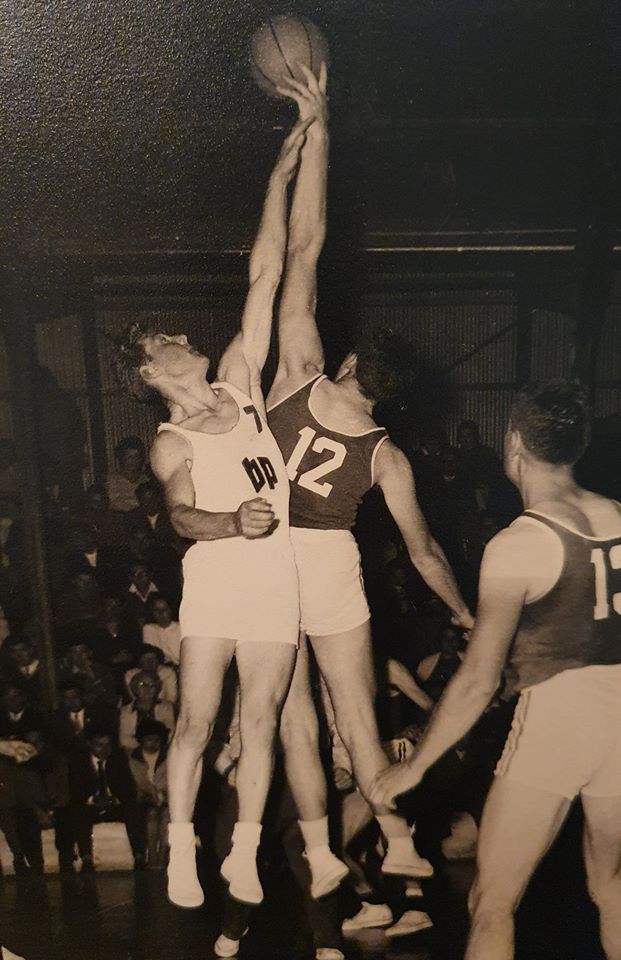

Swinging my little legs off the edge of the long wooden spectator bench at Forestville Stadium, sitting alone and waiting for my brothers and the Budapest men’s basketball team to reappear from the change-rooms, it still was a long way from tip-off time (below) for the 1963 South Australian winter grand final.

With my family’s deep Hungarian roots and my six brothers all strapping tall, athletic young men, it only was a matter of time before one of our ethnic community sporting teams found us.

Fatefully it was a man named Lojzi Ugody who met my parents, forming a fast and lifelong friendship. During World War II, Lojzi served Hungary in the military with distinction at the Russian Front of all places, making him a marked man when the Communists swarmed his homeland.

Australia was a wonderful land of opportunity to begin a fresh new life and one of the many things Lojzi did was start the Budapest Basketball Club, gathering migrant and displaced Hungarians, giving them a common purpose and a way to retain the ethnic side of their identity.

As a skills coach, Lojzi had few peers.

My dad started up the Hungarian Club in Osmond Terrace at Norwood and my mother was the choreographer and dance instructor for their migrant community. Her productions for the annual folk dancing portion of the Festival of Arts at Elder Park often were breath-taking, the women dancing with bottles of red wine on their heads, the men whirling dervishes of thigh-slapping, high-leaping extravagance. And very few of these Hungarian youths, press-ganged into service by parents keen to retain something of their displaced heritage, were actual dancers. Mum just taught them how to do it. And how to do it well.

In a city the size of Adelaide, it was inevitable then that Lojzi and my parents would meet and once he saw the size and athleticism of the Nagy brothers, with his great enthusiasm and infectious larger-than-life personality, the Budapest Soccer Club had zero chance of recruiting us for that other roundball sport.

Lojzi quickly became a very close family friend, keeping my brothers out of trouble by loading them into his VW ute on Saturday mornings to go pruning and gardening across the Hungarian community. They learnt invaluable life skills from their basketball mentor. He also had us making wine every year and some vintages turned out pretty spectacular. (Others were good for sprinkling on Friday’s fish ‘n’ chips.) But more of that later.

Importantly, Lojzi recruited the Hody brothers for his growing basketball club, two bona fide superstars who fled Budapest after the Hungarian revolution in 1956. Les was a 1952 Helsinki Olympic basketballer and both he and his brother John also would represent Australia. The Hody boys could play.

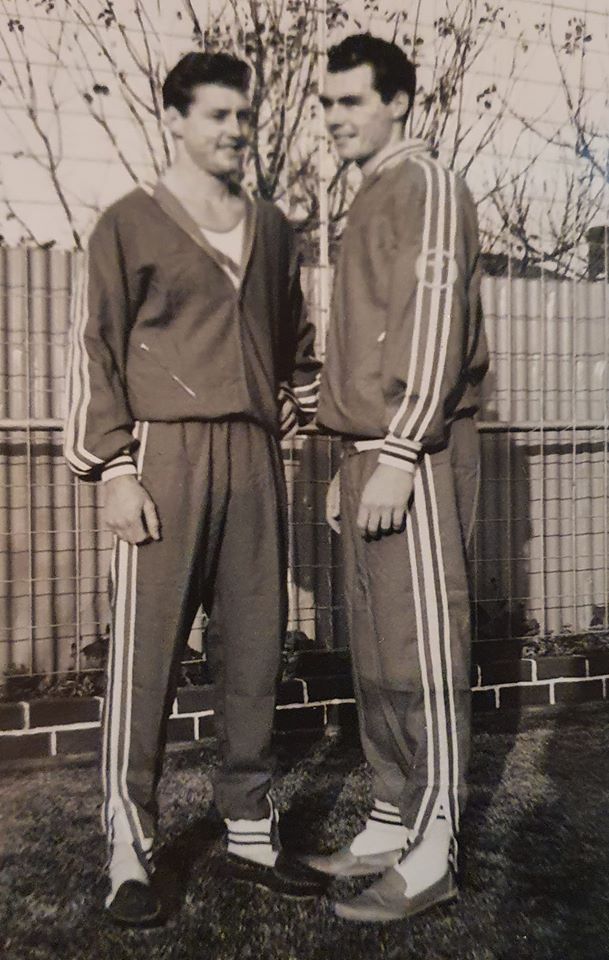

Andras Eiler was another genuine baller. My brothers Csaba and Geza (below), proud Prussian youngster Alfred Switajewski – who would go on to become a doctor, alongside another notable basketball player, Werner Linde – Henn Tennosaar who was recruited from an Estonia team which was winding up, making him suddenly available, with Gary Coombs and Tom Foote comprised Budapest’s “youth movement.”

Budapest lost its first grand final appearance in 1960 to A.S.K. – Adelaide Sports Klub, the amalgamation of Latvian clubs ALS and Venta. In 1961 and 1962, Budapest reigned supreme, beating A.S.K. for back-to-back championships. It was chasing the “threepeat” in 1963 against a South Adelaide club making its historic first appearance in the championship game.

They were a bit intimidating, Barry Wakefield wearing the same #7 as my brother Csaba and neither of them ever prepared to give an inch. You were always half-expecting a fight to break out between them.

Scott Davie was such a thoroughly focused young man and there was something terrifying about Dean Whitford too for a little kid of seven. (Later, I would learn of their deeply religious backgrounds and come to realise my childhood misgivings about them could not possibly have been any more misguided or unfounded. You could not hope to meet two finer gentlemen but, for now at least, they were the “enemy”.)

In those early days of the sport’s evolution in South Australia, there was far greater off-court camaraderie between players and clubs than currently exists. It greatly was fostered by the fact the matches were played on Thursday nights at Forestville Stadium so in one evening, you could see all of the greats of the game under one roof.

BACK-TO-BACK: Budapest's 1962 championship-winning team.

Therefore when “the Latvians” had a ball at their Latvian House in suburban Wayville, it was no surprise to see half the basketball community in attendance, with the West Torrens crew often leading the charge.

My parents somehow managed to purchase the house adjacent to our own at 5 Woodhurst Avenue in Hyde Park, knocking down the fence separating it from 7 Woodhurst and creating a monster back yard which eventually would house a full basketball half court. Someone from the family built a brick barbecue in the top corner of the joint back yard, so one of Budapest’s regular fundraisers was a barbecue extravaganza, with lights, music and dancing at the Nagy household.

As the family’s most dangerous and volatile brother, Csaba always had the role of bouncer. He is such a gentle soul now, it is hard to picture him admitting the stream of basketballers and their significant others through the front gates while turning back potential gate-crashers, and often forced into physical confrontations. Don’t recall him coming off second-best even once, though he was bloodied now and again.

Many of the South Adelaide players and officials would attend the Budapest Barbecues on those designated balmy Saturday nights in the Nagy back yard and it was where I met people such as administrator and photographer Barry Hannaford, refereeing guru Phil Yuill, basketball visionary and pioneer Frank Angove and, of course, Michael Ahmatt.

Michael was the first Aboriginal person I met, though at the time, South’s mysterious recruit from Darwin mischievously indulged speculations he was from any number of exotic locales. At that time in the Sixties, very few folks knew what the word “indigenous” even meant, let alone that Michael, or his teammate and great friend Joe Clarke were in some way different.

Michael was the first Aboriginal person I met, though at the time, South’s mysterious recruit from Darwin mischievously indulged speculations he was from any number of exotic locales. At that time in the Sixties, very few folks knew what the word “indigenous” even meant, let alone that Michael, or his teammate and great friend Joe Clarke were in some way different.

All I saw was two young men who were perpetually smiling, telling tall tales and just so much fun to be around. When someone accidentally played one of mum’s folk dancing records over the loud-speaker, Michael was quick to jump up and join her, mimicking her dance steps as the crowd separated to enjoy their impromptu show. Mum showed Michael some actual steps and he showed her some of his moves from an Aboriginal dance.

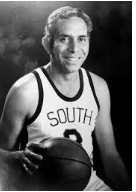

I was a little kid, allowed to be up late, mesmerised by this gentle man with the soft voice, wicked infectious laugh and compelling nature. I reckon it took me just a few minutes to fall in love with the man who was Michael Ahmatt, a love I still hold dear to this day. And that was well before he became the historic first Aboriginal Olympian with his selection for Australia ahead of the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games. To me, he was simply the Pied Piper.

So there I was, watching as the crowd which eventually would constitute a full house at Forestville Stadium, filed into the venue for the 1963 grand final between Budapest and South Adelaide. To my left, between the end of Court One and the back of the stand, sat the hot water tanks which fed the showers of the changerooms. I could tell even then that the stadium would be jam-packed to the rafters and I, once again, would need to climb atop the water tanks to have an unobstructed view of the court and the game. It’s usually where a whole pile of little kids ended up on big game nights. Distracted, wondering whether I should head there already, I was startled by a brief conversation which led to the most difficult question I’d ever been asked.

Spotting me sitting idly alone, Michael Ahmatt wandered down from the far end of the court where his South teammates were gathered, to sit down beside me. “Big game tonight,” he said, or something very similar. I was rapt to see him and even more delighted he had a few minutes to spare me ahead of such a major event. “So,” he started. “Who will you be barracking for tonight?”

Oh my Lord. What a question. What a dilemma. Michael Ahmatt, one of my childhood heroes basically was asking me if I would be barracking against him. “Well,” I started, summoning up whatever passed for wisdom in a little kid faced with such an enormously difficult challenge, “I will be barracking for Budapest because it is where my brothers play and it is my club.” Michael gave me a sad and disappointed expression, though I know now he was just pulling my leg. “However, I hope you have a great game,” I hastily added. “And if you should win, it won’t be a terrible thing or anything.”

Michael nodded, grinning as he rose, ruffling my hair. “That’s a very good answer,” he told me. I was pleased and proud at the same time. I remember it as though it happened earlier today, watching him walk back amid the enemy, his villainous South teammates, players such as devout Christian centreman Bruce Ninnis – who would name his son after that equally villainous Scott Davie – Bobby Hannam, Dean Whitford’s equally dangerous brother Brian. They were a scary bunch indeed and, as it turned out, bound for their first championship, Ash Koch coaching them to a 51-44 grand final victory which heralded the beginning of the end of the European dominance of South Australian basketball.

DON'T ASK - Yes, it was A.S.K. beating Budapest for the 1960 championship.

A.S.K. – “the Latvians” as they were perhaps even better known - bounced back in 1964, beating South in the grand final but the Panthers won the next two before playing West Adelaide in the following three grand finals, winning again in 1969. Starting with that fateful night in 1963, South played off for seven consecutive championships, winning four to briefly enjoy the prestige of being the state’s most dominant club. It always troubled me the club’s nickname was “the Panthers” yet its uniform was white shorts, white singlets with navy numbers and red trim. The “Snow Panthers” maybe? I’m guessing the basketball club appropriated the nickname from the SANFL Aussie Rules football team without adjusting its colours.

I know my mother was happy to see the decline of A.S.K., having perpetually been terrified for her sons having to face the size, might and temperament of players such as George and Mike Dancis, twins Aivars and Val Zarins – “I’m the better looking one,” Aivars informed me years later – and Eddie Ceplitis. The super silky play of Hall of Famer Inga Freidenfelds was something else we had to overlook as family members fearing for our brothers’ safety. That all changed substantially one year when A.S.K. did not nominate a team for the Summer Season of the district men’s competition.

In those days, there was a Winter Season, which steadily became the more important of the two, and a Summer Season played with a mid-season break for Christmas and New Year. As Winter became the most coveted championship, A.S.K. took a Summer off.

I cannot recall why but possibly there was a Baltic Games scheduled which they gave priority or maybe those older bodies just needed a break. Whatever, Mike Dancis wanted to play through summer so he joined Budapest for one season, on the understanding he would be cleared back to A.S.K. for the following Winter. With the Olympic giant now in Hungary’s colours, suddenly those big, nasty Latvian blokes of A.S.K. did not seem quite so ferocious anymore, Mike developing an almost freakish understanding with my point guard brother Szittya.

Even as a little kid, I was starting to show an interest in writing and, I don’t remember why, but my brother Eors bought me an old Remington typewriter from some knick-knack or antique store for my eighth birthday. Talk about helping someone head down a particular path, right? So when I wasn’t out in the back yard practising my shot, even as a tyke, I was hunched over a desk writing “stories” on my very own Remington.

The family would rave about these little pieces which I produced at a prolific rate. But, come on now, seriously, what kind of story is an eight-year-old producing? Looking back, I appreciate all the encouragement I constantly was given but actually, probably more appreciative of something my brother Huba said. Reading one of my little pieces which already had received marvellous reviews from others in the family, I could see he was trying to be delicate.

Craving more accolades, I pressed him from his reticence. “It’s not really much of a story, is it?” What the? It isn’t a work of modern genius? I’m not the next great writer, a boy wonder? What is wrong with this boy? Hasn’t he heard everyone else? “It just doesn’t go anywhere,” he told me. And yes, it basically amounted to something like: “Johnny was a short boy. He lived up the street. He loved football. The End.” Hmm. Maybe Huba had a point. It didn’t really say anything much, did it? So I can thank Eors for the typewriter, my family for its unwavering support and encouragement, and Huba for an actual criticism which changed everything.

Neither of them probably recall any of this, which often is how it is in life. Events or even the odd throwaway comment from an adult, a parent, a teacher, a coach, a kid, a pal, an enemy, which truly can influence and make a difference in a life, often only is recalled by the person on which it had the impact. “I said that? I don’t remember that.” Doesn’t matter, they don’t have to. What matters is how it impacted you.

In primary school, we used to get these very small writing books for new word spelling tests. They were the size of a small notepad today, the type that would fit in a shirt pocket. But they looked like a booklet with a cover and lined pages inside where we would complete those tests. It was a word for a line, then when you completed all ten words, you swapped your book with the kid next to you and you marked each other’s as the teacher spelt the words.

Often we didn’t fill up these books entirely and you might have one or two to spare from year to year. In all honesty, I am not even sure why now but in 1964, aged eight, I took my little spare writing book and a couple of pencils out to Forestville Stadium to watch the final of the Australian Championship between South Australia and Victoria. The Olympic team for Tokyo was being revealed after the grand final so it was a huge night on many counts..png)

During the game, I started making notes of what I was seeing. Don’t ask me why. All the stars of the era were involved. South Australia was boasting players such as Michael Ahmatt, Mike Dancis, Scott Davie, Dean Whitford and captain John Heard, a slender athlete from the United Church club, as its starting quintet. My brother Geza and a 19-year-old Werner Linde (pictured) were on the SA bench, along with warrior Alan Hare.

The Vics had some fairly notable names too, such as Lindsay Gaze, Barry Barnes, Billy Wyatt, Brendan Hackwill and, wait for it, Les Hody! Yes Les, the great Hungarian superstar who helped turn Budapest into an SA powerhouse, now was plying his trade in Victoria, along with his brother John. A young guy named Ken Cole also was there, though pre-Big V, still with NSW.

One of SA’s original Hall of Famers, Keith Miller, was coaching South Australia and super administrator and visionary Frank Angove managing the team. The tournament ran all week and SA beat the Vics 54-50 in their midweek meeting. But with another full house at Forestville, there was a lot of pressure on the local boys. New South Wales, led by John Gardiner - another player I idolised, along with spinning-top guard Denis Kibble – beat Western Australia 53-35 for third place, and Tasmania KO’d Queensland for fifth 69-47. Tassie had a couple of fairly useful players in David Claxton and Bryan Hennig.

Victoria led SA 22-18 at halftime and Miller gambled on his protégé Linde to start the second half. Linde, who in my mind remains the greatest basketball player the state produced, went off for 17 second-half points and it was free throws from Ahmatt and a two-handed underhand shot from Heard through the Vic defence which turned a 45-48 deficit into a stunning 49-48 victory. Fans stormed the court to carry Werner off and shortly after, he was named amid the twelve for the Tokyo Olympic Games. I wrote the game up in my booklet off my notes, as yet only associating my typewriter with fiction.

Soon after, Budapest staged one of its club barbecues in the Nagy back yard, Csaba manning the front gate and Alfred Switajewski joining my mum cooking the barbecue. I think it was at this particular barbie mum coaxed the shy medical student into chatting with a young lady named Joan who clearly had caught his eye, and vice versa. They married a few years later, but I digress.

Werner, Scott Davie and of course Michael Ahmatt were among the many crammed into our back yard that evening when my brother Geza suddenly remembers I wrote something about the Australian Championship final. He sneaks inside, finds my booklet and brings it out to read to the gathering of SA state players in attendance. I was, of course, mortified.

There had been an incident in the game between Les and Michael which ended up as a foul. Had it been called on Michael, it would have been his fifth but instead it was on Les. I just wrote it up as I saw it as part of the “match report” which drew great praise. Even so, I was truly embarrassed my little hobby had been exposed to all these star athletes of the day and wished the ground would swallow me up. That is until Michael, recognising how uncomfortable it all made me, tucked an arm around my shoulder and told me I should be proud to have given a more honest account than what appeared in the newspapers at the time. Remembering that again now, I can see where that too influenced me as a writer and reporter.

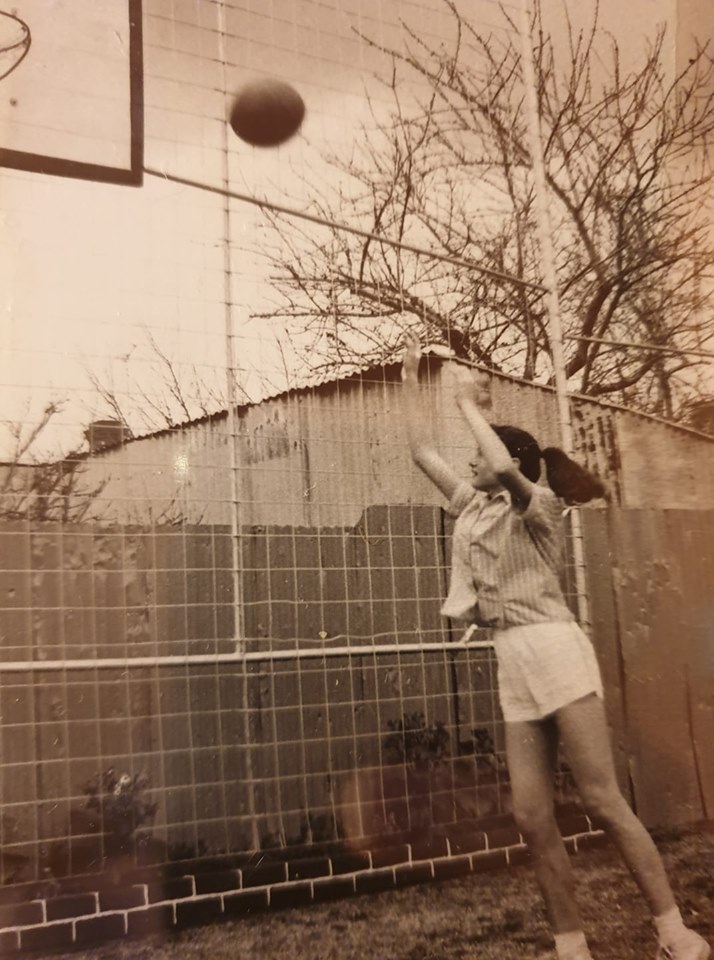

IN 1966, before my sister Hajnal (above) reached her sixteenth birthday, she won the Halls Medal as South Australia’s fairest and most brilliant women’s basketball player. She was a star of Budapest’s women’s team which Lojzi Ugody also took a great interest in. To win the medal while still fifteen was an extraordinary achievement, Hajnal that year starring for the SA Under-18 team at the national championship down in Tasmania.

All I recall from mum and dad’s stories from the tournament in Hobart is that SA was down by six in the final with three minutes left and won by six, a 12-0 run in which Hajnal was instrumental and fabulous. (And also that dad regularly entertained the other SA parents most evenings in their hotel lounge-room with his piano playing.) No-one knew my sister as Hajnal then. She went by her middle name, mum’s name Magdalena. So for those who didn’t know to correctly pronounce our surname Nagy as “Nodge”, she quickly became Maggie Naggie.

My brother Szittya also was making a name for himself for South Australia as a state junior and a youngster with a future on Budapest’s men’s team. Except basketball had slipped from his first love to second behind dancing. Of all the young Hungarian men corralled into folk-dancing by their parents, Szittya was something of a natural, probably inheriting mum’s flair for it. Mum obviously saw the talent latent within him and hooked him up with Leslie White’s Ballet School.

Born in England, Leslie White started dancing at the age of seven, finishing his training at the Royal Ballet School of London. He became a leading soloist with the Royal Ballet Company and toured all over the world with it. Coming to Australia in 1958, Leslie performed the role of Hilerion in Giselle, with Margot Fonteyn dancing Giselle. Falling in love with Australia, he stayed behind after the tour, opening his dancing school while also dancing on local television’s live variety shows twice a week. He performed with his own ballet company touring around South Australia and at two Adelaide Festival of the Arts.

Leslie became Szittya’s ballet mentor and by 1966, my brother was the leading soloist of the South Australian Ballet Company, which mostly was based at the Arts Theatre in Angas Street in the city.

One August night, on opening night of the company’s season of Coppelia, the ballet was well underway when a side door of the theatre quickly opened and closed. With Szittya (below) dancing the lead role, we as a family group had front row seats to the opening night.

In the Sixties and even into the Seventies, basketball’s medal counts were considerably different to the dinners and highlight footages etcetera of the modern era. Back then the medals – Halls for the women, Woollacott for the men – were an additional event on semi final night. With the regular season over, the first round of the playoffs was the semi final round, with third playing fourth in the first semi final and the loser eliminated. That was followed by the first versus second semi final, the winner through to the grand final, the loser having to play the first semi final winner for the chance to also participate in the championship game.

What would happen is the public address system would be activated in Forestville Stadium and during the warm-up for the first semi final, the third preference voting – each vote worth one point - was read out and counted. At halftime of the semi, the second preference votes, worth two apiece, were read out as the count continued. When the game concluded and warm-ups for the second semi final began, the first preference votes worth three each, were read out, the scores tallied and the winner of the medal formally announced. At halftime of the second semi final, the medal was presented to the annual winner of the sport’s highest individual accolade.

I know. It could be a distracted night for those contenders contesting the semi finals and also keeping an ear on the polling to check how they were going.

Unbeknown to the Nagy family, tucked up snuggly in the front row of the Arts Theatre watching Szittya wow the audience with his grace and athleticism, it also happened to be women’s basketball’s semi final night. The Budapest team, without much of a supporting cast for my sister, did not come close to competing in the playoffs so she was contentedly watching her brother doing his thing. As I said, suddenly the side door of the theatre opened briefly but when I glanced over, there was no-one in sight. That was because whoever opened the door to allow someone in, allowed that person in on their hands and knees. The performance was well underway so walking in was a definite no-no.

The theatre was dark of course so it took a short while before I realised someone was crawling in on their hands and knees so as to not disturb anyone or the performance. The person reached my startled father, whispering in his ear. Dad turned to mum, whispering in hers and she turned to Hajnal, beside me, to whisper something to her. Dad then slunk down out of his chair onto the floor, as did Hajnal, the two of them then also on hands and knees to follow the intruder out of the venue. They got to the side door fairly unobtrusively where the mysterious man knocked once, someone opened it from the outside and he, dad and my sister crawled out of the Arts Theatre.

The rest of us in attendance, which from memory was just Huba and me, looked at mum in the darkness, hoping for explanation. It wasn’t forthcoming until intermission when mum told us they had just counted the votes at Forestville Stadium and Hajnal had won the Halls Medal. Fortunately someone at the stadium knew we all would be at Szittya’s performance so Frank Angove had jumped into his car, driven like the clappers to the Arts Theatre, told management out front what had occurred, and they ushered him in through the side door.

So that was administrator extraordinaire Frank Angove in his suit crawling along the floor to get my dad and sister out and back to Forestville in time for her to walk up and receive the 1966 Halls Medal. She certainly had a good story to tell at high school the next day, as did we all.