FLASHBACK 138: Memories, circa 1950-1971

TweetAS revealed here last week, I've been buried in my PC banging out my memoir, inspired by colleagues Derek Pedley and Vincent Ross so here now is Parts Two and Three of Chapter One. Settle in with a cup of coffee because this is a longer read. Or, of course, don't.

CHAPTER ONE - Part Two

NOW that I reflect upon it, 1966 was a very big year for my family, a watershed year. It is kind of ironic my sister would win the first medal bestowed upon the modestly famous Nagy Brothers, while I reached double figures, turning ten years old and formally starting my own playing career.

My parents wanted me to have some sense of the arts and to not get lost alone in sport, so dad purchased season tickets to watch and hear the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra performing at Adelaide Town Hall. Dad actually purchased front row seats and we were there on Friday nights, soaking up classical music, just the three of us. Henry Kripps was conductor, Robert Cooper chief violinist, but occasionally a star foreign conductor would be brought in. On one such occasion, a renowned Hungarian conductor was flown to Adelaide to perform.

At the time, Adelaide still was blessed with not one but two Hungarian restaurants, the Csardas in Gouger Street and the Hungaria, tucked away in a corner of Hurtle Square. On the Thursday night, this highly-feted conductor dined at the Csardas in the city with my parents – dad’s own passion to be an orchestra conductor cut down by a little interruption called World War II. He clearly was impressed by how my parents, particularly my mother, were viewed and revered by our community.

The Town Hall was packed on the Friday as he took the ASO through the selected works of composers such as Franz Liszt, Brahms, Bartok. When the program concluded and he received his standing ovation, he acknowledged the orchestra, bowed to the audience once, then, quite deliberately, turned to face us, standing to his left in the front row.

He made a point of bowing to my mother, not once, but twice, as the raucous crowd roared and strained their necks to ascertain who the recipient was of such a grand gesture. I just remember feeling 10-feet tall with pride that yes, this was my mother. I tucked into her arm as we walked from the Town Hall to catch the bus home, and I am pretty sure it was the first time I understood my mother was someone very special, and not just to us but to the world at large.

He made a point of bowing to my mother, not once, but twice, as the raucous crowd roared and strained their necks to ascertain who the recipient was of such a grand gesture. I just remember feeling 10-feet tall with pride that yes, this was my mother. I tucked into her arm as we walked from the Town Hall to catch the bus home, and I am pretty sure it was the first time I understood my mother was someone very special, and not just to us but to the world at large.

The next time I noticed that occurred again in fateful 1966, at the 10-year anniversary of the 1956 Hungarian revolution. It was a cabaret or ball of some description, in the Bulgarian Club House or Dom Polski Centre, somewhere like that, filled to the brim with Adelaide’s Hungarian community.

The night’s program had singers, dancers and performers of all types but it was dad accompanying on the piano and mum singing who closed the show. Mum sang several beautiful and rousing nationalistic Hungarian songs which had the audience emotional and moved to tears. She finished with the Hungarian national anthem, the entire audience standing and singing along. They gave her what is known as the “vas taps” or “iron clap” which is a thundering ovation powerfully emotional and moving in itself. They didn’t want her to leave the stage.

Standing in the wings, once again I knew what pride felt like and that my mother was someone unique and special.

Make no mistake, my father was no slouch either. Trained in Hungary as a doctor of pharmacology, he could speak fluent Hungarian and German, learnt French along the journey, then taught himself Italian through his intimate knowledge of Latin. Contemplate that for a half second. He taught himself Italian through his intimate knowledge of Latin. I still can’t fully wrap my head around that today. It always blew the minds of the Italian migrants across the street, the Mastrullos, when dad spoke with them in their native tongue.

Woodhurst Avenue at Hyde Park was a pretty cosmopolitan street up our end of it, with a few Aussies such as the Cooks, Browns and Daniels, but then a hardy crew of Italians, Lithuanians, Norwegians and Greeks. Obviously out of necessity if nothing else, dad also learnt to speak English, with his penchant for puns doubly amusing given he was cracking word gags in his sixth language.

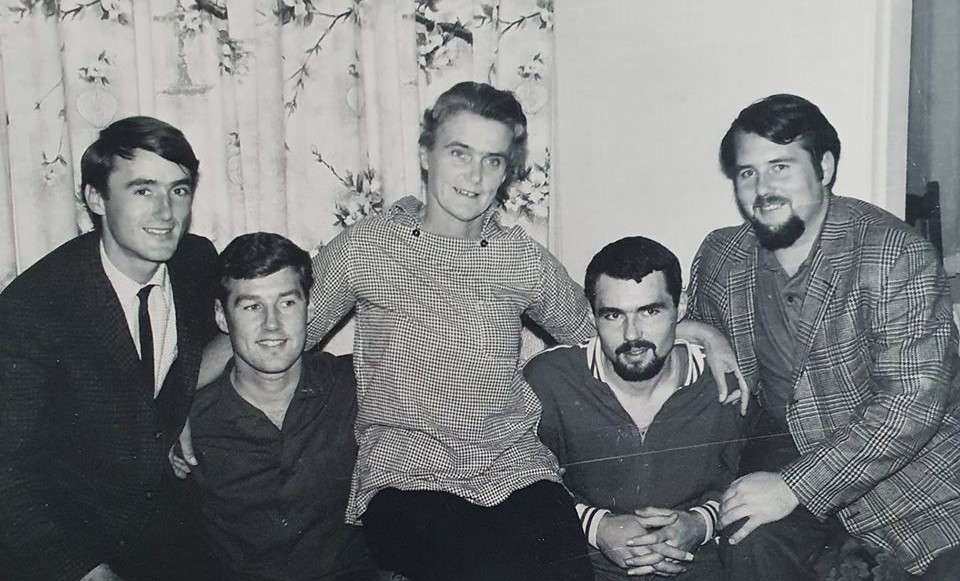

NAGY FAMILY: Living now in Woodhurst Avenue, the back row from left is Csaba, Akos, dad, Eors, Geza. Front from left is Hajnal, grandma, mum, me, Huba, Szittya.

There was a further historic moment in 1966 when dad, as president of the Budapest Basketball Club, orchestrated its merger with Norwood Basketball Club. It made such perfect sense to my father on multiple levels.

For starters, he could see that the number of future players that were sons and daughters of Adelaide’s Hungarian population was decreasing and, not only that, but as is the normal way of life, they were integrating and assimilating into society. Sustaining a Hungarian-based basketball club was going to steadily become impossible, an issue which already derailed the Lithuanians of Vytis but which the Latvians would not confront for many years yet.

Luckily in 1966, Budapest still was a powerful entity in the competition, making it an attractive merger proposition. An amalgamation with Norwood Basketball Club, considering Norwood at the time only was fielding teams in Division Two, was a no-brainer to my father. And to top it all off, the Hungarian Club which he also orchestrated, was situated in Osmond Terrace … at Norwood.

The stars could not have been more aligned. Dad’s plan was for the new club to be known as Norwood-Budapest for three years and for the Budapest name to then quietly slip into the archives and on to history as Norwood continued, hopefully to greatness. It was how it turned out too, with the Norwood club a few years ago honouring that part of its own rich history by naming the Most Valuable Player accolade for its leading women’s player as the Nagy Family Medal.

The new Norwood-Budapest team making its first appearance in the 1966-67 Summer Season, secured Les Hody back as its playing-coach, all four Nagy brothers – Csaba, Geza, Huba, Szittya – now part of the rotation. In addition the Mertin family of father and coach Ron, and his son and livewire guard Barry, plus others such as Wayne Hoffman, Lyn Gardiner and John Eddington also became part of the Norwood-Budapest fold.

Mario Giglio already had crossed from West Adelaide. Securing the robust Italian was a huge coup, with some considering him on par with Werner Linde at that time. I do vividly recall Mario hitting long shots with great consistency but more than that I often remember him lunging defensively to try create a steal, the offensive player blowing past him as a result, and him then wheeling around and knocking the ball free from behind the dribbler. A teammate would swoop on the loose ball and pass it to a now-free Mario. (My recollection is Mario enjoyed as many open lay-ups with that as he did fouls.)

The new uniform was pretty nifty too, with Norwood’s navy shorts and singlet, red numbers, capped off by a red-white-and-green Hungarian crest in the top left corner. The club now also was suiting a whole bank of junior teams but already striking what remains a common problem, even to this day – the great lack of coaching depth.

For the 1966 winter season, my sister Hajnal was drafted into coaching the Budapest under-12 boys team – the grade was known as “biddyball” then, under-10 and miniball yet to be a thing - and I probably was her most painful player. No. Not probably. Come on now, my sister was coaching, I was ten. Acting like a dopey kid was par for the course. Giving backchat to my sister just seemed cool at the time. Yeah. We all wise up as we grow up but wow, I must have been such a royal pain in the butt, especially because I also happened to be her best player.

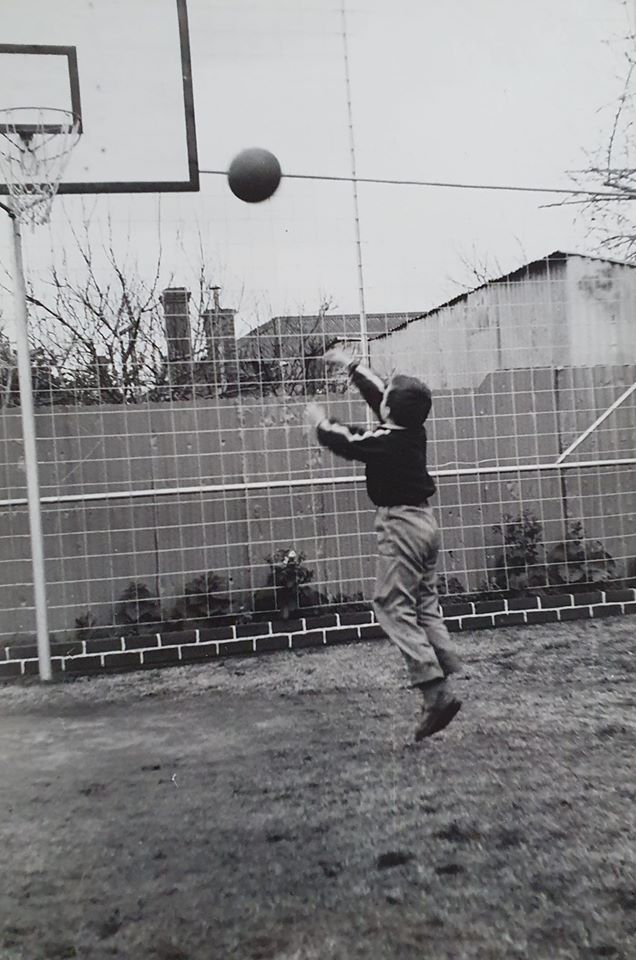

The team trained on Sunday mornings in our back yard on our grass half court, though we didn’t yet have the full cement keyway. It ultimately became a necessity as the grass under the basket took a regular weekly beating and barely recovered before the next week’s training.

The cement keyway came shortly after and was done by Adelaide’s cementing experts of the day, the Latvians. Dad commissioned them and they arrived one Monday morning, dug up the required area and poured us an accurately measured and properly conceived concrete keyway. They even did it in green cement so it would not look out too of place in the middle of our lawn. It was a quality job, lasting until my parents sold 7 Woodhurst Avenue some twenty years later and it was jack-hammered away, a new fence installed to separate the area into two homes once again.

Before the back yard basket and backboard first went up, another of our family’s Hungarian friends constructed and supervised the erection of a monster wire net back-drop which pressed up against the back fence of the neighbour’s property. It was massive but so brilliantly constructed that not even the highest winds affected it or its stability; quite the feat of do-it-yourself engineering. The wire netting ostensibly was erected to prevent errant shots from travelling into the neighbour’s yards, though it still happened occasionally with a bad bounce or an awkward ricochet.

FIRE UP! That's me shooting in the back yard. Check out the back wire netting AND also the battered "grass" under the basket. It was why we needed a cement keyway.

It was my job as the family’s youngest, to climb the fence and go collect the ball, so you would not be far wrong to suggest that entire back wire netting was erected for my benefit. Nonetheless, balls still did find their way over the fence and it almost always appeared to be happening in slow motion. A shot would clip the ring, bounce long toward our apricot tree, shave a branch and we would watch mesmerised as it sailed over the fence, helpless to prevent the inevitable.

I would climb the wire netting to the top of the neighbour’s fence, then step around to their side and jump to the ground, on my quest to find and retrieve the ball. This was exclusively my job but I don’t recall minding that much. What kid doesn’t like climbing and adventuring into an unknown neighbouring yard? Maybe Boo Radley lived there.

I used to derive some minor pleasure too when, only occasionally, I could scare Huba, Szittya or Hajnal by returning with the ball and looking grim, informing whichever of them had shot it that: “Oh my, you’re in BIG trouble.” I’d tell them the ball had crushed the neighbour’s prized azaleas, or smashed up their rose bush, broken some flower pots or something similar and that there would be hell to pay. The neighbours were enraged and storming around to inform our parents. It was fun watching my older siblings turn white for a minute or three.

In reality, the folks over our back fence who saw the most of our bouncing ball, mainly had a few fruit trees so no poor shot really caused any damage. And I don’t ever recall them being upset or concerned. We were raised to be polite and were always apologetic for any inconvenience our shenanigans may have caused.

While we may have been polite, we also had our share of mischief which, in the case of my siblings, was cultivated during their formative years at the Greta Migrant Hostel in New South Wales. The family arrived from Germany in 1950, flying on a DC4 Air Colombo aeroplane, in the air for 72 hours and in transit for five days. They departed from Bremenhaven in Germany and had stops in Rome, Cairo, Karachi, Bombay, Colombo in what is now Sri Lanka, Singapore and Darwin. From Sydney next, they were bussed to Greta where they arrived on Melbourne Cup Day, soon after Comic Court was first past the post.

Greta Army Camp was built at the small New South Wales town in 1939 for the training of soldiers bound for World War II. (My brothers loved finding shell casings and occasionally live ammo on the old firing range.) A decade later, “the camp” was transferred to the Immigration Department which utilised it as a reception and training centre for migrants from Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Ukraine, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Greece, Macedonia, Austria, Germany and Russia. It was quite the melting pot, built on almost 12 square kilometres of bushland and forest, wonderful for growing children in search of outdoor adventure.

Divided into two separate sections – Silver City (due to its huts of galvanised iron sheeting) and Chocolate City (brown-coloured oiled timber clad huts) – my family lived there until we arrived in Adelaide on Anzac Day in 1956. Times weren’t especially easy, most of the husbands and fathers working away from home during the week, in places such as Sydney, Cairns and the Snowy River.

GRETA CAMP: From left, mum, grandma and Aunt Anna, outside living quarters at "the camp."

While dad was working in Sydney during the week, mum was nurturing and raising seven children and looking after her mother-in-law to boot. She even doubled as “the camp” hairdresser. The family photographs from that period always immediately make me think of the Von Trapp family from “The Sound of Music,” even down to the lederhosen tunics my brothers all wore. Greta also is where I was born, one of dad’s weekend visits obviously proving extra fruitful.

More than 100,000 migrants passed through “the camp” between 1949 and 1960, about 9,000 Europeans there during our sojourn. Polish-born basketball identity Nick Buvinic, who was heavily involved with Norwood, then with wife Helen co-owned the National Basketball League’s Hunter Pirates in Newcastle, was at Greta during the same period. Nick’s wife Helen is the sister of Denis Kibble, a Newcastle basketball dynamo I also loved watching play. It was rare in those early days to see these stars from other states, you just knew of them by name and reputation. Denis was in the New South Wales team in Adelaide for the 1964 Australian Championship and was gracious enough to have an extended chat with the youngest of the Nagy siblings as they waited for South Australia to finish its morning training session.

More than 100,000 migrants passed through “the camp” between 1949 and 1960, about 9,000 Europeans there during our sojourn. Polish-born basketball identity Nick Buvinic, who was heavily involved with Norwood, then with wife Helen co-owned the National Basketball League’s Hunter Pirates in Newcastle, was at Greta during the same period. Nick’s wife Helen is the sister of Denis Kibble, a Newcastle basketball dynamo I also loved watching play. It was rare in those early days to see these stars from other states, you just knew of them by name and reputation. Denis was in the New South Wales team in Adelaide for the 1964 Australian Championship and was gracious enough to have an extended chat with the youngest of the Nagy siblings as they waited for South Australia to finish its morning training session.

All of my brothers have only the fondest memories of “the camp” but to me, of course, they are just wonderful stories, not vastly different to the ones they tell of when we first moved from Greta to Adelaide. We initially lived in Dulwich and, apparently on days when the horse racing was on at Victoria Park Racecourse, some of my brothers would head over Fullarton Road, climb into the trees and watch from perfect, unobstructed viewing points. And yes, they carried me up and I was sitting there too, cradled among them, watching the horses galloping past. Do I remember any of that? Not at all. However I am in no doubt it happened, and regularly.

I was lucky enough to be selected in the unofficial “under-12 state team” in 1966 to play in the annual best-of-three series against Victoria. It was held in each state on alternate years and we were at home at Forestville Stadium for this one. The team was coached by Grant Surfield and wasn’t called South Australia but “District.” The fun part of that for me is the District select team wore red singlets with the words “District” in blue and our numbers in gold – the state colours. Meanwhile actual SA state teams, which started from older age groups, back then wore white uniforms with blue numbers and gold trim. Yeah, go figure. (Maybe someone at South Adelaide was recommending the colour scheme?)

In juniors at that time and throughout my junior career, United Church – which later would evolve into Sturt – and West Adelaide were the dominant clubs. North Adelaide and Centrals (formerly CY, then later becoming Glenelg and even later Noarlunga City Tigers) would be around the mark battling for finals spots and all of us had great sympathy for the Latvian kids who played for A.S.K.

Those poor bastards had to go to Latvian School every Saturday morning after playing, so A.S.K. teams always had the earliest timeslot every week before they scurried off. As if going to school Monday-to-Friday wasn’t enough of a burden. These kids had to also go on Saturday mornings.

While we felt it cruel and unusual punishment, it still is worth noting the Latvians lasted the longest as an ethnic club, long after Budapest, Vytis, Estonia, Polonia and the rest were only memories. Striving so hard to retain their national pride and culture obviously paid off.

The District team (above) had several terrific players who went on to have prominent careers, including Jeff Fullwood, Chris Stirling and Melvin Need. West Adelaide’s John Bew, who would have enjoyed a great career but for injury, also was on the team, along with Ivars Zvirgdzins from A.S.K. As a first year, I didn’t expect to see much action because Jeff, Chris, Melvin, John and a couple of the others already were very accomplished and second year players. But it was a huge thrill just to be part of the whole experience, a very decent crowd attending Forestville to watch the series.

The Summer Season for 1966-67 rapidly was upon us but our little Budapest under-12 boys team suddenly did not have a coach. And this was despite the Norwood merger. My sister had spat the dummy – probably something to do with some pain-in-the-arse kid she was always having to battle with – and the club president was not amused. While I still was being read the Riot Act, dad taunted the question at me: “Who is going to coach the team now?” In a moment of ten-year-old bravado, I boldly proclaimed I could do it. Playing-coaches abounded all over the place, I reasoned. Even our Norwood-Budapest men’s team had a playing-coach in Les Hody. I’m guessing now dad decided to teach me a lesson as, in an apparent moment of madness, he appointed me playing-coach of the under-12 Budapest boys team, still shy of my eleventh birthday. He likely intended to continue to hunt for a proper coach while my little ego took the bruises and bumps it so richly deserved for a couple of weeks.

I wasn’t silly enough to think I had the expertise to teach the other players anything skillwise but I did have a few ideas of what we could do. From memory, I asked to have our little team included in the under-14 team’s Sunday practices at Forestville Stadium while I firmly believed – and still do – that there’s nothing better for basketball players than to play. I won’t digress here into my theory players today train far too much and play far too little but I’ve always believed kids not born with inherent court sense, and that’s the majority, will only build it by playing and playing, and playing some more. So I invented “set matches” which is what we called the 3-on-3 halfcourt competition I organised for my team every Saturday afternoon after we played our Norwood-Budapest fixture at Forestville Stadium.

Post-game we marched from Forestville under the tram bridge, down the alley street next to the train line from Goodwood station, along Victoria Street to Goodwood Road, crossed together when it was safe, then walked down to Mitchell Street and home to 5 (and 7) Woodhurst Avenue at Hyde Park. We would break for lunch in the back yard, relax, then split into six 3-on-3 teams … which wasn’t all that easy because there were only eight boys altogether. The back yard half court, with its cement keyway, now had proper sidelines and a centre line clearly marked by several garden hoses and a couple of tent pegs I prearranged each game-day morning. Mum had sewn red numbers onto a couple of white cotton singlets so between those and our regular uniforms, we had two playing sets.

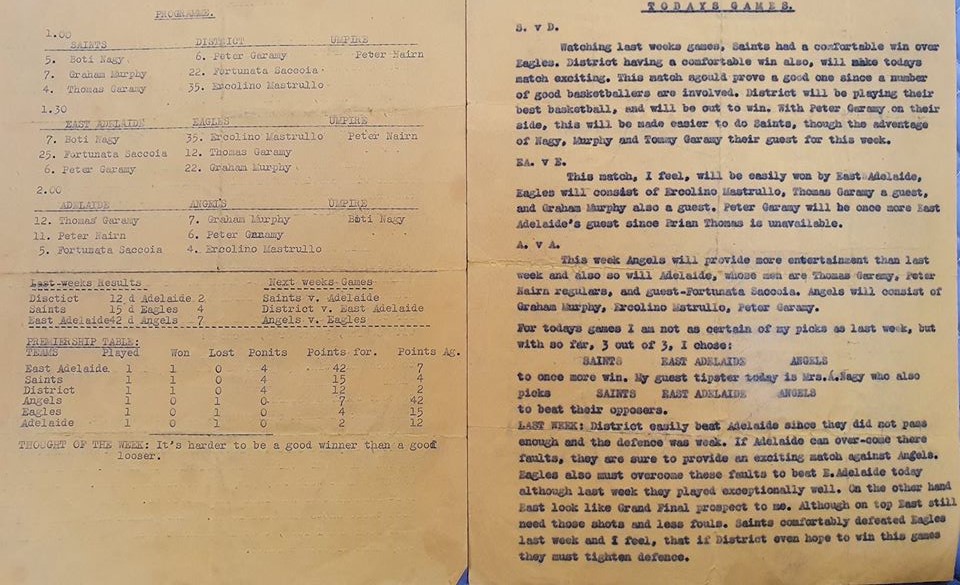

It worked like this. The eight players, Peter Garamy, Thomas Garamy, Graham Murphy, Ercolino Mastrullo, Peter Nairn, Fortunata Saccoia, Brian Thomas and myself virtually played for all six teams, namely Adelaide, Angels, District, Eagles, East Adelaide and Saints. It was 3-on-3 so the two players not involved refereed the game. Then we’d break before playing a second game with revised team lists, then a third with the teams again rearranged. If you weren’t playing, you were reffing so again, learning more about the sport. We basically played away the afternoon before parents rocked up to take their basketballed-out kids home.

Dad brought home a stack of yellow paper used in the pharmacy at Royal Adelaide Hospital where he worked. Using three pieces of carbon paper, I squeezed in four of the yellow pages into my Remington to type up a weekly program. Then I repeated the process so there were eight copies, one for each boy. It paid to grab an early copy because the fourth carbon was a blurry one to read.

YELLOW SHEET: An example of the weekly program I typed up twice each week.

I updated the program’s premiership ladder each week, leading scorers etcetera, mirroring the state’s men’s program as much as possible. Having yellow paper was magnificent because the weekly programs for the men’s competition were printed on yellow paper.

By the time we reached the grand final between Saints and East Adelaide – played in front of a large crowd of parents and neighbours - we had a few more players in John Kanas and Brian Hocking and were playing a lot of basketball every Saturday. And because this was 3-on-3 and we didn’t add subs until the finals, everyone saw a lot of action and rapidly improved.

So much so that Norwood-Budapest never did find a replacement coach to take over from me as we reached the final four playoffs for the first time, won our first semi final but lost the preliminary final 22-29 to Salesian College, doubling as Glenelg (or Central’s) under-12 team at the time. I scored 18 but could not get us over the line. It’s a long time ago but it still burns, obviously. Mum watched the final and when the siren went, the players all shook hands and I led our chant of “three cheers for the opposition,” then ran and cuddled into her, crying disconsolately. It was the only time I cried at a basketball game.

PART THREE

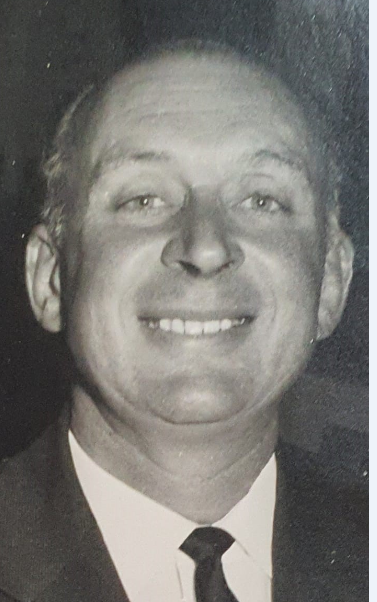

Bill Spear (pictured) was the fatherly gentleman coaching West Adelaide’s boys team at the time. He also watched our game and made a beeline for me afterwards, waiting until I pulled myself together to approach my mother and I.

Bill Spear (pictured) was the fatherly gentleman coaching West Adelaide’s boys team at the time. He also watched our game and made a beeline for me afterwards, waiting until I pulled myself together to approach my mother and I.

He graciously shook my hand and congratulated me on what he described as a remarkable, if not unbelievable achievement. He was full of praise for me and what I did as a player and amazed I also coached the team to such success. I wasn’t feeling awfully successful just at that moment but he certainly made me feel so much better. This time it was my mother cuddling into me and feeling proud of her 11-year-old, which also made the day less disappointing.

People such as Bill were very important to me growing up. They just showed me great kindness and it was kindness for its own sake. Albert Leslie, one of the era’s great players, often would stop his car on Victoria Street when he saw me walking along the last leg of the road to the stadium ahead of a morning match. He would pull over, offer me a lift and chat all the way to Forestville Stadium. He was the first true gentleman I met. Tim Hisgrove was a playing rival at North Adelaide but there was never a time Tim’s father saw me walking along Victoria Street when he didn’t stop his car to give me a ride. I was very used to the walk; raising eight children, travelling from war-torn Europe, working three jobs in Sydney before we ever got to Adelaide, meant dad never had the time to learn how to drive, nor the inclination. So “driving” wasn’t a big deal in our family.

Geza and I never learnt, though Csaba and Eors were quick to do so. My oldest brother Akos and Szittya eventually got around to it, as did Huba and my sister. Huba was hilarious when he got his licence but moreso when he purchased his first car and drove it up in front of the house. He came inside to get me, then we sat in his car for a good 10 minutes while he sat behind the steering wheel, moving it from side to side making car engine noises. Vroom vroom.

Eventually we did a trek around the block, then mum got the same treatment. Later, I accompanied Huba as he drove up to the drive-in theatre at O’Halloran Hill, “to scope out the route.” That night we went back there to watch the latest James Bond movie, “Diamonds Are Forever.”

Of course, that was all in the near future. Back in that 1966-67 men’s Summer Season, the good news was that the new Norwood-Budapest entity was having a flyer. It didn’t start with too much promise when they lost the opening game of the season, but from there they won 15 consecutive matches to finish on top with a 15-1 record, South Adelaide next on 13-3, West Torrens 11-5 and West Adelaide 9-7.

South’s greater playoff experience was a significant factor in its second semi final with Norwood, just as West Adelaide’s was in the first semi final. Both the Panthers and Bearcats won, South advancing to the grand final, West to the preliminary against Norwood.

This was the finals series when all four Nagy brothers were playing together and a time during which the match of the night was broadcast live on radio station 5DN by the wonderful Fred Heaton. There was a raised box built at the end of Court One at Forestville to accommodate Fred and his co-hosts, and when the rest of us could not attend, huddling around the radio in the lounge-room to hear his call was an absolute must.

Those radio calls left me with two very distinct memories. One occurred on a night when the boys had an early game and mum expected dad and their sons to be home by a particular time. We had and still have a very distinct “Nagy family whistle” which, when you heard it meant something was afoot and it was time to gather as a group. Everyone in the family knows the tune.

CONGRATS: South's Michael Ahmatt was among the first to congratulate Budapest after it won the 1961 SA grand final, shaking Bryan Hennig's hand in this picture.

So mum is starting to fret about the whereabouts of her husband and sons while Fred is giving his halftime summary of the match 5DN was broadcasting. Fred takes a pause and in the background we can hear dad’s “Nagy family whistle” coming over the airwaves, loud and clear. “They’ll be home in about 20 minutes,” I told mum, knowing that was how long the walk home took. “I just heard dad give the whistle.” Captain Von Trapp eat your heart out.

The other memory was during the call of a Budapest game when my brothers were all on the court together. Heaton excitedly was word-painting the action with: “Nagy with the ball, passes to Nagy, he gives it off to Nagy who spots Nagy open but he gives it to Giglio.” Heaton paused. “Giglio? What’s he doing out there?” Not sure about any other listeners that night, but we were rolling around the floor at home. Loved Fred.

The preliminary final was going to be a tough one for Norwood-Budapest because apart from a string of talented players such as Alan Hughes, Doug Romain, Clive and Keith Perring, Rodney Trengove, Russ Terrett and Howard Black, West Adelaide also boasted American centre Bill Stuart and the incomparable Werner Linde.

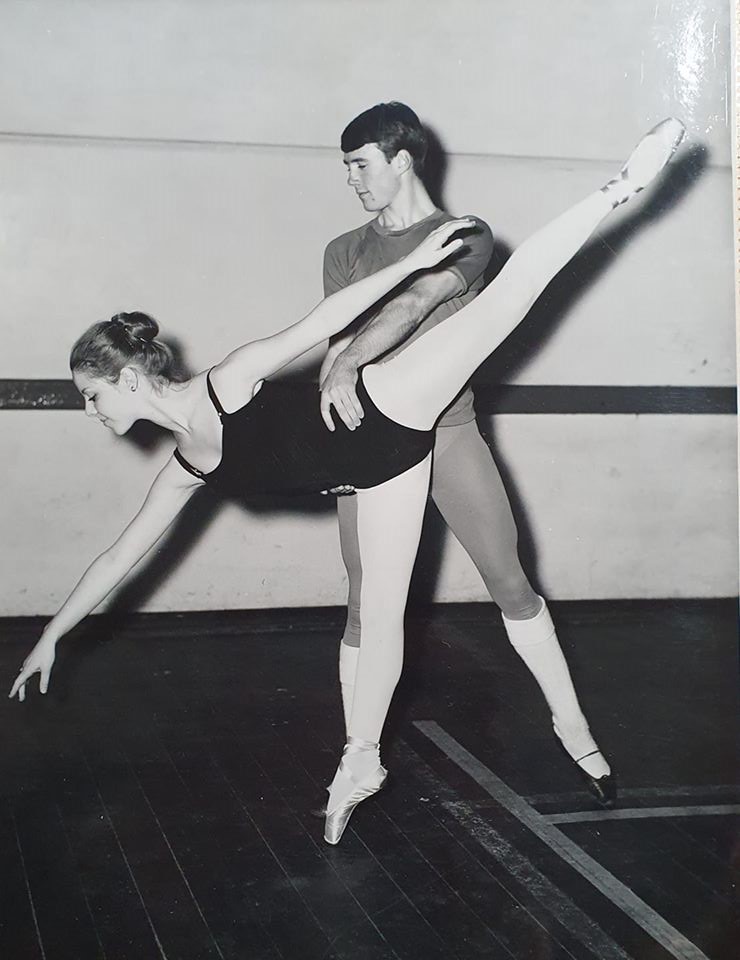

Already an Olympian in 1964, Werner in 1966 had just won the first of his three Woollacott Medals as the fairest and most brilliant player in South Australia, led the competition’s pointscoring and was nearing the top of his game. There simply was no stopping him. Of course, if he didn’t have the ball then stopping him became moot. My brother Szittya was as fast as greased lightning and ballet made him even lighter on his feet. He had a simple strategy. Werner couldn’t beat Norwood if he couldn’t get the ball.

Szittya, who probably now is the least known of my brothers for what he did as a basketball player, played the perfect defensive game on Werner by absolutely denying him the ball all match. Wherever Werner went, Szittya was there first, able to deny the pass to him, then recover equally swiftly to avoid losing him on a back cut. Werner became increasingly frustrated, having to pass the ball into court after Norwood baskets or on sideball possessions, just to handle it.

Szittya containing him to four points was one of the more remarkable achievements in our family’s basketball history. He was completely exhausted as the siren sounded on a resounding Norwood win, spent and with nothing left in the tank. Showered and finally at home, when he collapsed into the sofa, he was dead to the world.

In them thar good olde days, when your senior men’s team reached the grand final, the curtain-raiser for the night was a clash between the respective clubs’ under-12 boys teams. My team may not have made it to the grand final but I fancied our chances of beating South, which did not reach our finals. Plus the excitement at our halfcourt competition on Saturday was through the non-existent roof, all of my team aware they would be playing in front of a sell-out crowd at Forestville Stadium. Even Arthur Newley was excited for me.

Poor Arthur. The father of two of Australian basketball’s modern greats Brad and Mia, I idolised him and his burgeoning game every time I watched West Torrens. I had my share of heroes on other teams apart from Budapest, Mike Megins, Alan Hare and John Horsell three of them at North Adelaide, South’s Michael Ahmatt of course and Peter Buss, who was a muscular star at Torrens alongside Arthur. Now there was a guy with a physique. (Torrens also had a player who scared me a little, a bruiser with sharp elbows and unafraid to use them named Jeff Coulls. But more about Coullsy later.)

Poor Arthur. The father of two of Australian basketball’s modern greats Brad and Mia, I idolised him and his burgeoning game every time I watched West Torrens. I had my share of heroes on other teams apart from Budapest, Mike Megins, Alan Hare and John Horsell three of them at North Adelaide, South’s Michael Ahmatt of course and Peter Buss, who was a muscular star at Torrens alongside Arthur. Now there was a guy with a physique. (Torrens also had a player who scared me a little, a bruiser with sharp elbows and unafraid to use them named Jeff Coulls. But more about Coullsy later.)

Arthur was working in a bank on Unley Road, not too far from Unley Primary School which I was attending. Once I became aware of that, every now and then I would ride my bike to the bank after school and wave to Arthur from outside. This lovely gentle soul never failed to acknowledge me, indicate for me to wait, finish whatever he was doing or with whoever he was serving, then come outside for a brief chat. He always acted interested in how my team was going, who we were playing, how was school going, that sort of thing. He was just bloody brilliant to a little impressionable kid and I would always ride off home feeling on top of the world.

I say “poor Arthur” because obviously he would have copped relentless stirring and derision from his workmates about his little fan showing up again. I suspect he really must have inwardly cringed any time he saw me pedal up. But he was never anything other than totally attentive and generous with his time for me and I love him to this day for having such a kind heart. When I think about it, I was truly blessed that so many in our basketball community respected my family and extended their kindnesses to me. Arthur said he was looking forward to seeing me play before the grand final that week so I was absolutely devastated when I came down with the measles midweek.

There was no showcase for me in front of 1500 people sardined into Forestville that Thursday night for the men’s grand final. In fact I was so sick, I have no recollection of who coached my team or how the boys went.

I do remember that Norwood beat South in the men’s grand final so that the club’s first season as this amalgamated force and my father’s vision paid off handsomely. I also recall that Szittya again was the hero when he was fouled in the final half-minute with Norwood ahead by one. He calmly slotted both pressure free throws for a three-point lead and that was the final margin, South’s desperate attempts to score quickly not paying off and the celebrations on in earnest. (But I still was glad Michael Ahmatt had a good game.)

LOJZI Ugody (left) guaranteed a level of notoriety for our family by introducing it to basketball but our parents were heavily into the arts. As mentioned, dad was studying to be an orchestra conductor before the war and played the piano, while mum had dance in her veins and possessed a powerful and cathartic singing voice.

LOJZI Ugody (left) guaranteed a level of notoriety for our family by introducing it to basketball but our parents were heavily into the arts. As mentioned, dad was studying to be an orchestra conductor before the war and played the piano, while mum had dance in her veins and possessed a powerful and cathartic singing voice.

We always had a piano in the house and before we ever had the wherewithal to purchase our first television set, singalongs as dad tickled out the tunes were a regular post-dinner event. In fact, we were not half bad. Von Trapps? Well, maybe not.

Now I cannot recall how this came about but I do know when mum wasn’t teaching the Hungarian folk-dancing crew on Saturdays at the YWCA near St Peter’s Cathedral, the other place they routinely rehearsed was in one of the studios Channel 9 had in Tynte Street, North Adelaide. Whether somehow that led to a connection with the TV station or someone from within it, all I know is our post-dinner singalongs suddenly developed into a two-song rehearsal for us to appear on one of the Adelaide Tonight variety shows. I can’t recall much about it other than standing near the piano with my siblings, dad playing and us belting out a couple of numbers in front of a live studio audience. It was all a bit overwhelming to be honest.

Next thing I knew, my sister Hajnal was identified as having a great voice and returning to television as a soloist. (For some reason, I keep thinking it was on an afternoon kid’s program and on Channel 7.) Anyway, she appeared on the program and shared the bill with three gawky siblings named Barry, Maurice and Robin Gibb, who also sang a bit. They kicked on with it though and didn’t do too badly in the end while we all became lovers of the Bee Gees music and Hajnal continued to sing, but mainly in the shower. That wasn’t our only brush with fame away from sport, either.

Next thing I knew, my sister Hajnal was identified as having a great voice and returning to television as a soloist. (For some reason, I keep thinking it was on an afternoon kid’s program and on Channel 7.) Anyway, she appeared on the program and shared the bill with three gawky siblings named Barry, Maurice and Robin Gibb, who also sang a bit. They kicked on with it though and didn’t do too badly in the end while we all became lovers of the Bee Gees music and Hajnal continued to sing, but mainly in the shower. That wasn’t our only brush with fame away from sport, either.

Where we lived at Hyde Park bordered the next suburb, the substantially beautiful and rich leafy suburb of Millswood. One of Australia’s greatest ballet dancers, Sir Robert Helpmann lived in Wood Street at Millswood. Wood Street is one street over, parallel to Woodhurst Avenue. At the time, it was chalk and cheese once you passed intersecting Jasper Street, heading along Wood toward Northgate Street and the glorious Victoria Avenue. Szittya’s reputation as the principal dancer of the South Australian Ballet Company was growing with every performance and soon came to Sir Robert’s notice in his capacity as co-director of the Australian Ballet.

One Sunday afternoon, I answered a knock at the front door and a kindly older gentleman was standing there, asking whether my parents were in. It was Sir Robert, though I didn’t know that until I caught him in a couple of movies soon after, “The Quiller Memorandum” and in “55 Days in Peking” where he was playing a Chinaman.

Just from his general deportment though, I could tell he was a person of some importance. My parents entertained him in the lounge where he also spoke at length with Szittya, Sir Robert keen to recruit him to the Australian Ballet.

Szittya was studying radiography, playing basketball at the highest level, while also being the state’s best male dancer. It was a great deal of commitment but Sir Robert made it clear the door to the Australian Ballet, which toured the world as well, was always open to him. Whether that inspired him further or not, his ballet stature simply grew, his on-stage leaps and pirouettes breath-taking stuff and always drawing massive ovations. No surprise then that a short while later I again was opening the front door on a Sunday afternoon, with the great man standing there. This time he brought along a friend to help in the recruiting process, Rudolf Nureyev.

PAR FOR THE COURSE: Szittya's burgeoning reputation as a dancer spread very quickly.

The first Russian artist to defect to the west, Nureyev was regarded as the doyen of male lead dancers anywhere in the world, his teaming with Dame Margot Fonteyn the stuff of ballet legend and folklore. My mother thought he was the greatest, Szittya did too and few would argue with either. Whether Nureyev was performing in Adelaide or just visiting his friend Sir Robert escapes me now. But I do know when I opened that door I was mightily impressed.

Unfortunately dad was at church and Szittya wasn’t at home so they only spent a brief time chatting with my mother who turned in a magnificent performance of not acting over-awed. Mum felt Szittya would be devastated he missed on meeting Nureyev so we kept that visit to ourselves, Helpmann no stranger to our doorstep as he tried desperately but ultimately unsuccessfully to lure my brother to the Australian Ballet. Szittya had other plans, intending to travel to Hungary, then on to England, which he eventually did.

MAKING wine was an annual summer ritual for the Nagy household. Before I was old enough to even notice, wine grape vines were planted all along our driveway at 5 Woodhurst Avenue, providing a year-round canopy around to the back yard. The vines continued from there around the back and all the way along to 7 Woodhurst. I suspect Lojzi Ugody had something to do with it because he and a few of his Hungarian wine buff cronies always led the annual event.

It was a weekend exercise, with picking the bunches of grapes the first chore but hell, don’t mix the chardonnay grapes with the muscat – are you crazy? Next they were loaded into this massive green-metal vat and I would then be lifted into it to stomp the grapes with my feet. Oh yeah, this was sophisticated wine making at its finest.

I loved it, stomping around like some tin soldier on a parade ground, squishing grapes underfoot and between my toes. "Do I detect a faint hint of tinea in this riesling?" Once I was tired enough, I would be lifted out and the real press would then go to work. There was much hilarity and joy associated with this process and I was always allowed to turn on the vat tap to drain one bottle of grape juice as my reward. It tasted the sweetest and divine, but drinking it that day was a must.

I corked it once, it fermented overnight and exploded in the morning. Much better to drink it on the day and spend the next day exploding in the toilet yourself. Lojzi then stored the wine in barrels in a cellar somewhere and, as stated earlier, occasionally it was quality stuff when it was ready for corkage. And sometimes it was ghastly too.

MUM AND THE FOUR 'OLD ONES': From left, Eors, Csaba, Geza, Akos.

The reason my parents purchased 7 Woodhurst Avenue was for the “four old ’uns”, namely Akos, Csaba, Eors and Geza. Already young men, they needed their space. Mum, dad, grandma and the “four young ’uns” - Huba, Szittya, Hajnal and I - lived at 5 Woodhurst. Dad’s mother died when I was still quite little. She was buried at Centennial Park, my father distraught. The family still was standing around the grave, comforting dad long after the other mourners paid their respects. I remember asking mum why dad was crying and she said that this was now where grandma would rest forever. I took dad’s hand and suggested he cheer up, grandma’s grave beneath a lovely tree which had birds singing, even as I spoke. And at night, I told him, she could watch movies across the road at Hiline Drive-In. Frankly, I felt she had it pretty good. It was one of the times dad lifted me into his arms and hugged me for all he was worth.

THE FOUR 'YOUNG ONES': From left, Szittya, Hajnal, the author and Huba.

Another time was at the Royal Children’s Hospital where I had a bump of some description removed from under my tongue. The surgery done, I was over the whole hospital routine and ready to go home. When dad arrived in the ward on his lunch break at the Royal Adelaide, I could not have been happier. He leaned down to hug me and I gripped him so tight, I was not letting go until I was home in my own bed. He laughed at my determination and lifted me out of the bed, holding me with one arm and calling for the nurse. She checked as he gathered up my belongings, me still hanging onto him for dear life, and it was OK for me to go home early. Within what seemed seconds, we were out of there and in the back seat of a taxi, bound for Hyde Park, mum stunned as he brought me in on his arm. That was when I let go of him, much to his amusement. “He wouldn’t let me leave him,” he told her.

In such a big household, it was inevitable knowing everyone as intimately as you might in a nuclear family was impossible. Akos was 22 when I was eight and the first to move out, so we only actually found each other as adults. The furthest apart in age, mum spoke often how concerned she was for Akos when she fell pregnant with me, knowing he again would suffer the most in terms of time she could exclusively devote to him. With six sons and a daughter already, breaking the news the family again would grow from seven children was something she dreaded.

The story goes that when she told him he was about to have another little brother or sister, his face lit up and he delightedly exclaimed his joy with: “Mum! How much easier will it be for you to be able to cut an apple into eight pieces instead of seven?” Who knew the best line to ever come out of Akos’ mouth would happen when he was 14? Suffice to say when he invited me to have a “brothers bonding” day at the football one Saturday, I was blown away.

We bussed into the city where he led me to a terrific fish and chippery in some back lane and bought me the first hamburger of my life. It’s a lunch I still recall with some joy. Then we bussed to Unley Road and walked to Unley Oval to watch Sturt host South Adelaide. It was 1964, Sturt was on its way toward being an SANFL powerhouse, John Halbert an imposing on-field presence.

But South had a compelling figure organising much of the action. The player in question was its captain-coach, Neil Kerley, who quickly became another of my childhood heroes. What a hard ass he was, and Ian Day was nipping around, snapping goals.

But South had a compelling figure organising much of the action. The player in question was its captain-coach, Neil Kerley, who quickly became another of my childhood heroes. What a hard ass he was, and Ian Day was nipping around, snapping goals.

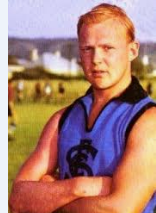

I was loving my first live Aussie Rules footy match. Brother bonding ended at halftime after I spotted a cluster of school friends, all avid Sturt supporters, and asked if it was OK to join them. We were at the northern scoreboard end and Akos also had found a group of his drinking buddies so was cool with it. My new crew settled down at the southern end of the ground near the Sturt cheer squad for the second half and that afforded me the chance to become a secret fan of Sturt’s multi-talented Rick Schoff (pictured).

South won the premiership that year but Sturt’s golden era was not long in coming and I attended many of its home matches at Unley Oval. I respected the club and so many greats I saw live regularly such as Bob Shearman, Brenton Adcock, John Tilbrook, John Murphy and Daryl Hicks. But with virtually all of my friends Sturt supporters and the Blues on the verge of their most dominant era, hearing daily about their greatness became tiresome.

It was much easier to follow Neil Kerley, which is how when he crossed to Glenelg I became a lifelong Tigers supporter. (Though when I say “lifelong”, I mean that if my life only lasted 20 more years after that.)