FLASHBACK 140: Whipped into shape

TweetWELCOME back. I hope you checked in yesterday and enjoyed Part 1 of Chapter 2 of my work-in-progress memoir. Here's Part 2 today and thanks for the encouragement and support from so many of you.

Working on the book has kept me from having my "finger on the pulse" of our sport for a while but I will jump back onto that again soon enough. In the meantime, here is Part 2 of Chapter 2. I hope you enjoy it and thank you to those readers and friends who assailed me to post this.

Your support means everything and never is taken for granted.

CHAPTER TWO - PART TWO

MY brothers were interesting characters growing up. My oldest Ákos was who I knew the least, though I know he played a lot with me when I was a tyke. But he was first to move out.

Csaba was something of a he-man growing up, buying weights to work on his muscle development and conscious of his good looks and ability to attract female interest.

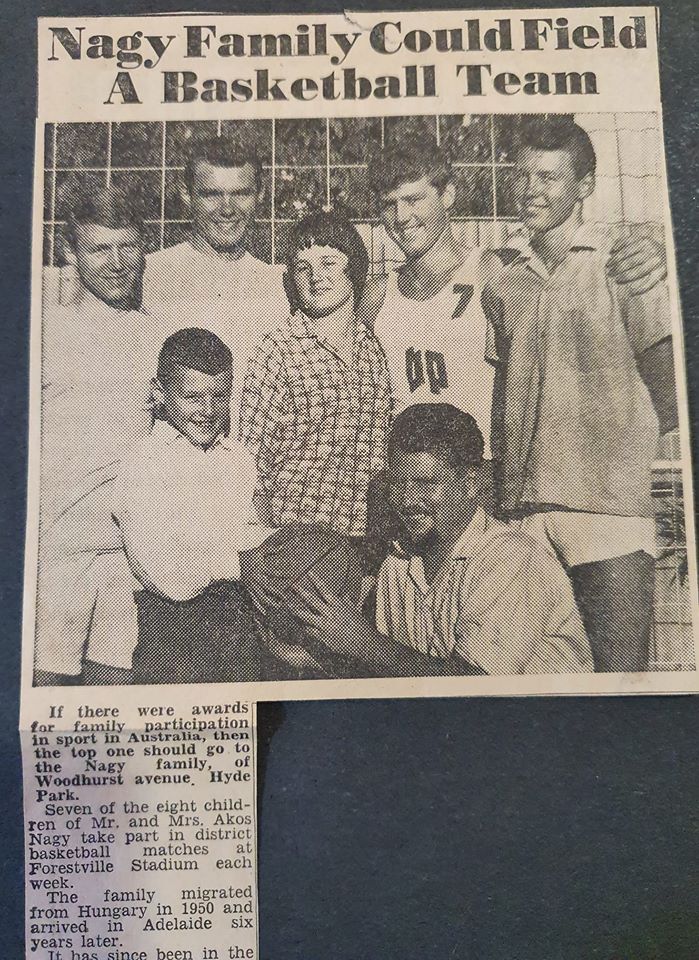

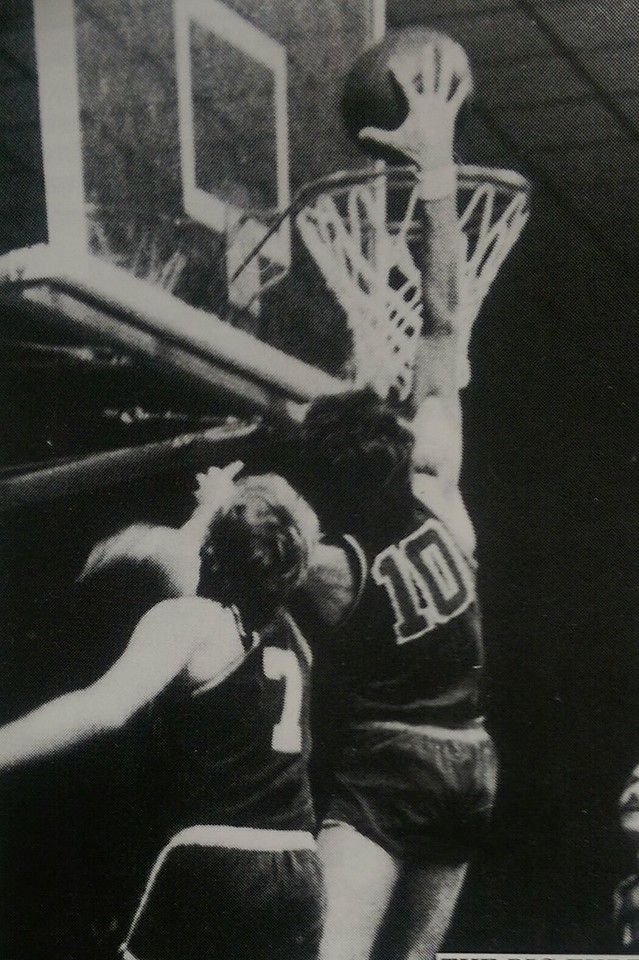

GOOD NEWS: The family's basketball connection was huge and considered newsworthy.

He was a mischievous guy and a fun one, though he suffered from “white line fever” on a basketball court and woe to you if you did anything untoward to any of his younger brothers.

You throw a ’bow at Geza, scrag Huba or trip Szittya and next time you were grappling for a rebound or setting a screen, Csaba was knocking you back through three generations of your family tree.

NAGY BROS: Back: Geza, Szittya, Csaba. Front: Huba. Harm one and Csaba had your number.

That said, his frustrations post-game when he smashed holes in stadium change-room doors or plasterboard walls were more to do with aggravations at his own limited skill set and with referees, than anything an opponent ever did. He was a tough guy, playing with reckless abandon, diving for loose balls, skidding into stands, forever risking life and limb because, frankly, he knew no other way.

One Saturday afternoon after attending a matinee screening of some swashbuckling movie, he returned unimpressed at how much wailing a character did after being tied to a post and given twenty lashes with a whip. “Surely it couldn’t hurt that much,” he reasoned, going inside the house and returning with his Hungarian bull whip.

Quick segue. Growing up, Guy Fawkes Day was a big annual event in November when virtually everyone in the neighbourhood and right across the city and state set off the fireworks and crackers they purchased in the lead-up. The evening was sprinkled with fireworks across the night sky and the ongoing sound of small explosions as crackers were set off or thrown.

While I still was quite young, fireworks were not something the family budget extended to but Csaba was not one to let the neighbourhood know we could not afford such a dubious luxury. So as night fell, he took his bull whip and stood in the middle of our vast backyard, cracking that thing for all he was worth. For all intents and purposes, every crack of his whip sounded like a cracker being set off. He was out there for an hour and just kept cracking that whip.

The next day, the Nagy Family and its almost inexhaustible supply of crackers was the talk of the neighbourhood.

The whip was a gift from a family friend Sandor Tamas, an older Hungarian gent living at Cheltenham, way across town. Csaba and Eors had a room each in his house for whenever they visited on weekends to help him build structures in his home and yard, such as his magnificent grotto aquariam and backyard aviary.

It was time to put the whip to use, Csaba believing the movie character was over-acting because being lashed could not possibly be as painful as he made out. My brother took off his shirt and said he wanted 20 lashes to find out for himself. Of course, he wasn’t completely silly, choosing me – the youngest and weakest – to take the whip and administer the punishment. (One of the older boys may well have flayed him with that whip.)

I told him I didn’t want to do it because he would get mad at me and he responded that he’d be mad at me if I didn’t do it. Caught between a rock and a hard place, I shrugged and he turned with his hands above his head, clutching one of our grapevine poles, bare back staring at me. It was a big target.

Holding the handle firmly, I threw the whip back and brought it forward with as much force as I could muster, the leather slapping fiercely against his skin with an almighty thwack. Fairly certain his scream of pained agony could be heard down most of Woodhurst Avenue, I didn’t think it prudent to stick around. There were definitely not going to be 19 more of those.

His scream was my cue to throw the whip and run like crazy and hide. He quickly was in enraged pursuit but that one lash was so painful, he could not find his quickness before I was gone, in and under mum and dad’s bed before he even knew I was in the house. The only sound I could hear from the garden was the riotous laughter of the rest of my siblings.

On another occasion when I still was a little kid, as one of my “big brothers,” Csaba decided to teach me how to defend myself in the event of a physical assault. Somewhat wary, I told him I could take care of myself so he held out his hands, palms facing me, asking me to punch them.

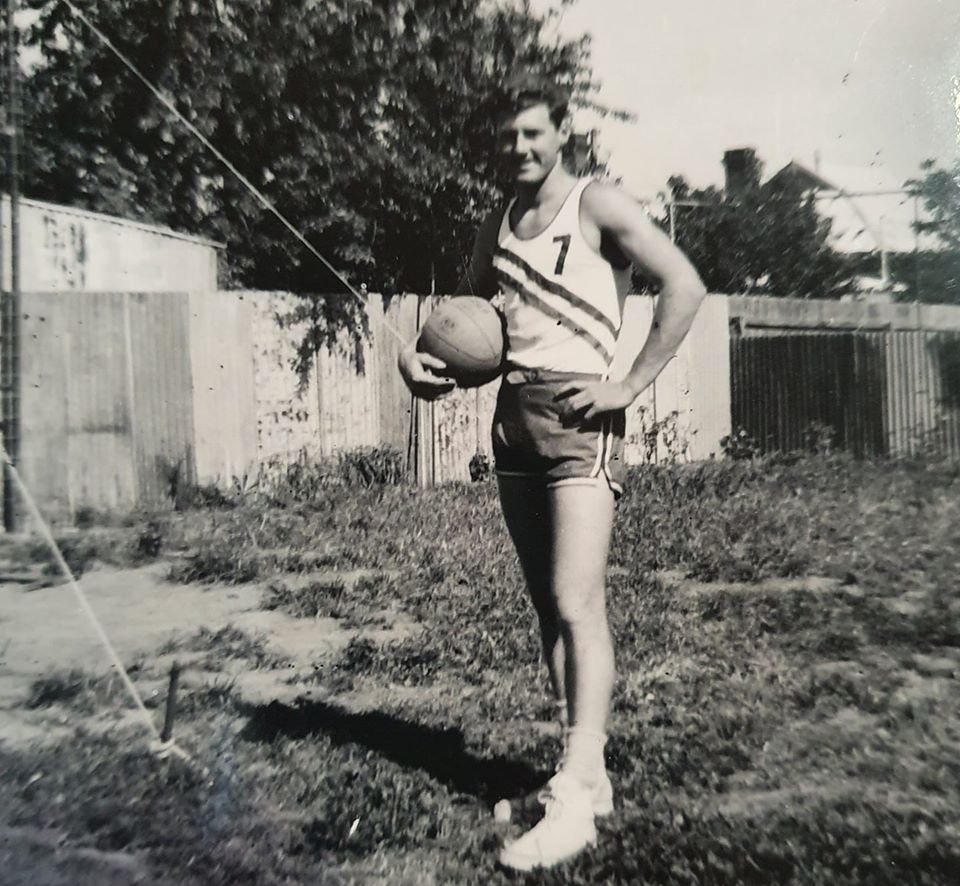

WHIPPING BOY: Csaba in his Budapest gear in our backyard, pre-lawn. Would you whip him?

I did and he seemed reasonably satisfied. I thought that was it but then he asked what I would do if I couldn’t use my fists. In what scenario would that happen, I wondered aloud? So Csaba lay down on the floor, probably to appear less menacing, and told me to straddle his torso. I did as asked and he reached up and grabbed by hands. “What can you do now?” he inquired, well pleased my fists were incapacitated. I leaned forward and bit him on the chest.

He released his grip immediately, screaming, my cue to disappear, Csaba soon in hot pursuit. Fortunately he never figured out that under mum and dad’s bed was a terrific place to hide till he calmed down. Not to paint an inaccurate picture of him, because frankly I adore him, Csaba never in any way truly threatened me.

When giving chase, I always heard him laughing, mildly cussing at me with “you little bugger.” When he married Margaret Griffin, the young lady from the corner chemist who completely besotted him, they insisted I be in the wedding party, invoking an old Hungarian tradition where I led the entourage down the aisle at the start, and out of the church at the conclusion.

It was a role that filled a little boy with great pride.

My relationship with Eors had much to do with my eventual move into writing and, to a lesser extent, journalism. Apart from being the brother who gifted me that first Remington typewriter, well before that he lived through his own personal life-or-death drama.

Suffering from a rare lung infection, he spent a year in hospital, my parents daily fearing the worst and some experts insisting he had tuberculosis and demanding he be shifted to a hospital catering to it. Dad firmly believed Eors did not have TB and that exposing him to patients who did risked infection and with it, his young life.

He steadfastly resisted such overtures and ultimately, Eors correctly was diagnosed and had lung surgery. During those many long months consigned to a hospital bed, I often was Eors’ companion for the day. He had encyclopedias and books of all shapes and sizes to show me, taking great pleasure teaching me new words, even as a toddler.

In hindsight, those times with him unquestionably tweaked my interest in words, in reading and writing. The typewriter present capped it off. Mum’s gift for storytelling also helped immensely. She read books to me every night and invented yarns of her own, with her littlest boy often the star of them.

Mum’s ability to more colourfully recount an event, turning dullish black-and-white occurrences into a kaleidoscope of vibrant storytelling, initially left me confused. I remember her retelling a story of earlier one day when the horse-drawn wagon slowly wound its way along Woodhurst Avenue with its old driver calling out “Bottles, bottles, bring me your old unwanted bottles.”

I misheard him and she played up to it, suggesting I hide because he was looking for me and calling out for assistance to find me. She was smiling so I knew it wasn’t true. I just tucked in behind her skirt at the front door before he pulled up and she laughed, taking out a sack of old bottles for him.

Over dinner though, her recount of the “incident” was far more exciting and colourful, the horse rearing up, the reinsman leaping from his seat to restrain it, and inside, me shivering in my boots needing reassurance he wasn’t indeed looking to take me away somewhere. I lived it and though initially her version confused me, I did enjoy the way she told the story. It had a pizzazz the reality did not.

Between Eors expanding my word power and mum my imagination, becoming a writer of some description arguably was inevitable. Writing match reports and previews of our 3-on-3 “set matches” competition for the weekly yellow sheet game-day program also became a key element in the whole process.

Allowed a modest amount of pocket money, I used it to purchase comicbooks, originally drawn in by the Superman and Batman heroes of DC. Some of my brothers introduced me to the art-form via their war and western comics, which supplemented the John Robb novels I read about his cowboy hero Catsfoot.

My brothers also handed down their Phantom comics. Now there was a hero with such a consistent back story as to be irresistible.

Mighty Mouse and an entire colourful array of Disney comics featuring Donald Duck, Mickey and Minnie Mouse, the notorious Beagle Boys and Scrooge also took my imagination to new places. As Ákos moved out, then Csaba married and followed suit, Huba and Szittya moved across to 7 Woodhurst Avenue and both Hajnal and I had our own rooms.

This was a major development. As a baby and toddler, I shared my parents’ bedroom before being allowed to move in with Huba and Szittya in their shared room. When my parents announced that move, my two brothers sat me down to explain “the rules” of the room, which included the very serious “you can only fart under your blanket.”

I soon realised that rule did not apply to either Huba or Szittya though.

My own room meant an entirely new regime. Hajnal had an ink pad and a number of stamps it was possible to adjust to say different things. I spelt out the words “COMIC LIBRARY” on one and used her stamp-pad to stamp the words on each item in my growing comicbook collection.

On selected days during each set of school holidays, the rest of the kids in the street were aware the “Comic Library” was open and they could visit my very tidy bedroom and borrow from my comics, neatly on display.

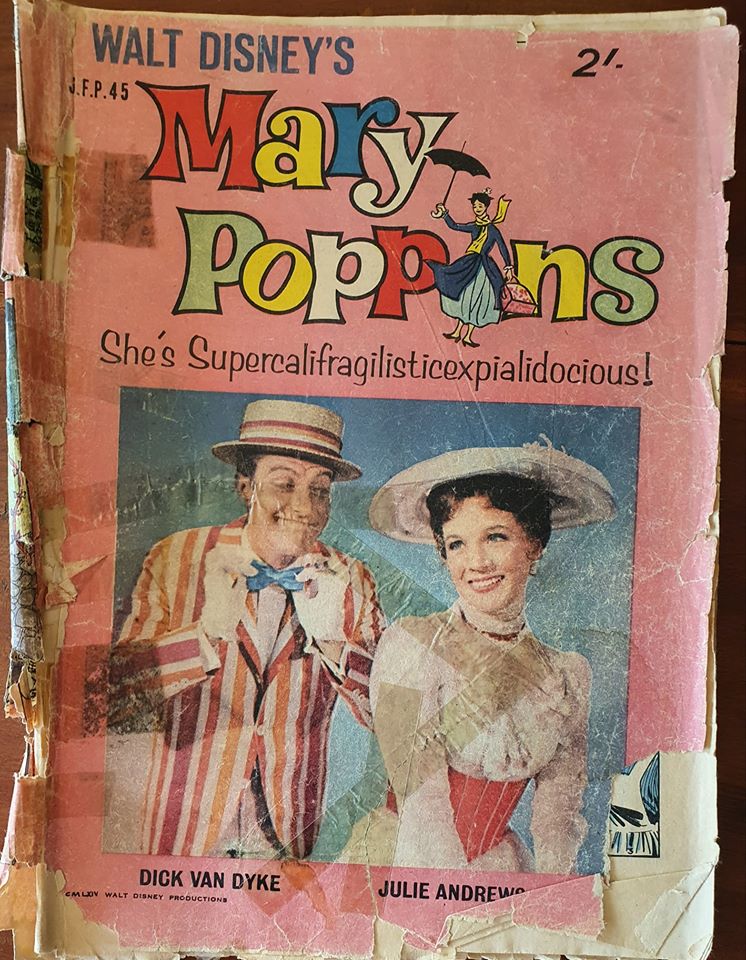

I signed them out, the kids took them home and returned them at the next library session, usually swapping for a new comic. Amazingly, everyone looked after the comic they had on loan and they rarely returned in anything other than excellent condition. Except my Mary Poppins comicbook.

I love Julie Andrews, but especially in that role and, of course, as Maria in Sound of Music. Disney produced a comicbook which came out shortly after the movie (which I still love to this day) and for some reason, that one took a bit of a beating.

It was a small price to pay for the chance to share my passion for comics with the kids of the neighbourhood but I did take Mary Poppins out of circulation. Still got it too (above).

A horse-and-wagon idling down our suburban street collecting bottles was not unusual for the time. Fresh bread also was available from a horse-drawn wagon – a horse once bit mum on the arm in our street. I’m guessing it didn’t like her embellishing her stories – and bottles of milk were delivered overnight and waiting on the front doorstep in the morning.

At school, we drank a small bottle of milk before recess time. Lactose intolerant? What did that mean?

For my brother Geza, I was the one for whom he brought an extra baseball mitt so he had someone to throw a baseball with in our backyard. He could throw that thing for hours and, unfortunately, that meant I had to as well. To be honest, I always hated it, much preferring to have a few shots on our basket with him.

He was six foot four – about 194cm – and the tallest of my brothers. In his era, he was playing centre, as were guys in the 6-2 range such as South’s Bruce Ninnis. That’s why the Dancis brothers of A.S.K. were so feared. George and Mike genuinely were big at 6-7, though today, even that is short for a centre. But they also were solid BIG men.

At Geza’s height, going up eventually against centre players such as 7-footer (213cm in today’s lingo) Tom Bender was more than modestly challenging. The fact he often outplayed far bigger men spoke volumes to not only his talent, ability and experience but also to his basketball smarts.

Representing South Australia against the visiting US college elite of the Big Ten All Stars, he dominated these bigger, younger, athletes in their first match-up, rebounding like a man possessed. He conspicuously struggled in the re-match, it only coming to light post-game that any time a shot went up, he not only was the Big Ten’s main focus but that its nearest player would grab him by the crown jewels and hold on firmly till the ball was secured. The basketball, I mean.

The tactic was such a shock for him, it proved a very effective way of restraining him and a “strategy” rarely encountered or for which there was no obvious easy counter. Of all the Nagy brothers, and sister, no-one had a sharper basketball mind than Geza. The moves he showed me were gold. It easily beat throwing a baseball into a glove till nightfall ended the futile exercise.

Szittya was a state junior captain, Geza routinely selected for South Australia for senior Australian Championships and Csaba regularly picked for “District” teams, unofficial state sides which toured places such as New Zealand. Hajnal was a star at both state junior and senior levels and the youngest ever Halls Medallist. Even I have state junior representation on my meagre playing resume. But Huba? Nope.

He had to work his butt off to reach the best version of himself as a player because of our family, coming through, he had the fewest credits. Every afternoon after art school, he was straddling a reinforced bench before jumping up onto it. He made himself a weights vest and added more and more weight into its array of reinforced pockets, increasing the degree of difficulty for the jumps.

Eventually he also sent away for ankle weights. He would be jumping for ages, then go into the backyard and throw down every sort of dunk imaginable. He would shoot jump shots for an eternity. I know, because I was the one sitting on the log waiting for him to finish so I could have my turn on our court before it was dark.

Finally when he ditched the weight jacket and/or the ankle weights, it meant his session almost was done. Without any weight restrictions, he looked as if he was flying when he resumed dunking and jumpshooting. Huba developed one of the smoothest, purest jump shots you could ever hope to see. It was copybook and he was deadly. Lord knows he worked hard enough to make it so.

As for dunking? Only ever saw him throw down one in-game dunk, despite how much time he spent refining the skill. It was at Apollo’s scoreboard end during a regular season game for Norwood-Budapest. A teammate fired up a shot, it hit the back of the ring and bounced straight up. Huba came flying in from somewhere, rose high above the pack and smashed down a massive tip dunk. I jumped out of my seat while the majority of fans at Apollo Stadium either were bemused or bamboozled.

It was a case of “what just happened?” Or “what did we just see?” Dunking in the local competition in the late Sixties actually was not a “thing,” just something showy for the warm-ups. Huba not only dunked it but tip-dunked over a pack. There was a definite delay, a hush and then a rousing smattering of applause as what he just did finally registered. Hmm. Won’t do that again anytime soon!

That Huba made himself the family’s most famous basketball player by winning three Woollacott Medals in that era speaks volumes to his drive and determination. It also gave me inspiration and practical evidence of the benefits of hard work.

Huba, who wore number 10 for Norwood, won the Woollacott Medal as South Australia’s fairest and most brilliant player in 1968, 1970 and again in 1972. At the time, the greatest Aussie Rules football player I’ve ever seen, Barrie Robran, was wearing number 10 for North Adelaide in the SANFL and winning the Magarey Medal in 1968, 1970 and 1972. I loved that symmetry between my brother and Barrie Robran (below) who not only was an incomparable footballer but a charming, gracious, polite and lovely human being.

A few years ago, Basketball SA revisited its medal process for awarding its medals, to also reward those players who lost on a countback. Because the medal was about “most brilliant” it originally was deemed one first preference vote worth three points was superior to three votes gleaned through a second preference vote worth two and a third preference vote worth one. Thus in the event of a tie, the player with more first preference votes won the medal.

BSA reviewed this process, supporting the contention that to score a second and a third preference meant that player was in a match’s top three votegetters twice, which had to be as good as being the best player in a game once. The association scoured its records and the Woollacott Medal lost by Huba to Werner Linde in 1969 on a countback additionally was awarded to him.

That makes Huba the most successful South Australian medallist in the game’s history in SA as its only four-time Woollacott Medallist. (South’s Mark Davis holds the record with five Woollacotts but Mark won them as an American import.)

Apparently Huba was painfully shy as a kid which is why mum gave him a list and regularly made him go to Mr Binny’s corner deli to draw him out of his shell. Anyone who knows Huba now – an Elvis impersonator, one-man Bee Gees show, Dean Martin in a local version of the “Rat Pack” – knows mum’s plan wildly over-achieved.

I liked accompanying him because Mr Binny had a sister Marta who also worked in the deli and seeing her made my day, any day. Eventually he sold the shop to the Mastrullo family who lived in Woodhurst Avenue. Ercolino, who later abbreviated his name to Eric, was a good friend growing up and for years I had a crush on his sister Tina. You know, the whole “older woman” thing. She was 14 when I was 12. The best soup brews in an older pot – old Hungarian saying.

The Mastrullos were my first exposure to real earthy Italians and I loved them. Playing in their backyard late one afternoon, they invited me to stay for dinner so I quickly ran home across the street, seeking permission.

That dinner was something, home-made pasta with the Mastrullo nonnas actively involved in the preparation already made it special. This was food I’d never previously experienced. But more than the food I remember the initially startling loud, raucous verbal exchanges of the family’s adult members – dad Tony, grandpa, mama and nonna – going hard at it.

Thumb held against the other fingers on the hand a la an inverted bird’s beak, and the shaking of that wrist to make a point. It sounded as if they were having a furious verbal fight but with the kids hardly reacting, I soon realised they were just having a passionate conversation.

The discussion probably was about the pasta sauce but it was full on and very quickly I loved it, finding such loud antics amusing even if at first they seemed foreign and disconcerting. It drew me to Italians in general and some of my best friends even now come from that ethnic origin.

Oswald Panozzo lived around the block from Woodhurst Avenue, on the corner of Mitchell and Wood Streets. One afternoon while Eric, John Kanas and I were in our street snacking on loquats from a neighbour’s tree, Ossie came pedalling around the corner from Mitchell Street, riding his little tricycle on the footpath. We automatically became very protective of our street from this interloper.

We pulled him up and inquired what he thought he was doing coming into our street uninvited? He started to cry, turning his trike around and heading back out of our territory as fast as his little legs could pedal. The three of us were quite satisfied he wouldn’t pull that stunt again anytime soon.

Except about a quarter of an hour later while we still were dining in the street, this time on almonds, Ossie returned with another biggish kid, Trevor Hayes, both with toy swords tucked in their belts and carrying a bamboo stick each. They were grim and serious, looking like something out of Huckleberry Finn, clearly prepared for war.

The sanctity of our street at stake, I told them not to come a step closer until we organised. I huddled with the other two and we ran to our respective homes to change.

I came back out wearing my cowboy hat, twin-holstered gunbelt – armed with two cap-guns - and the wooden rifle Eors carved me for my previous birthday. I can’t recall what Eric and John wore when we assembled again minutes later, beyond the fact they too had on their most menacing outfits and Johnny was wearing a cowboy hat.

As our street kids’ unofficial leader, I knew I had to make the first move as we all faced off. Trevor Hayes lived in Mitchell Street between Woodhurst and Wood Streets, with a reputation for toughness which preceded him. But we were defending the street’s honour and could not be cowed, so I raised the wooden rifle above my head, yelled “charge” and ran hard at this pair of Mitchell Street hoodlums.

Trevor raised his bamboo stick and reciprocated and the two of them ran at us at full bluster too. Fortuitously for all of us I suspect, a car suddenly turned into Woodhurst Avenue from Mitchell Street. The driver beeped its horn at us and we scattered, the three of us back into our respective houses, the two of them scampering back into Mitchell Street and out of sight.

The great battle for the bragging rights to our street effectively was fought and won. At least, that was how John, Eric and I interpreted it the next time we hooked up to play brandy. We sure showed them.

As it turned out, Trevor Hayes went to a different school, while Ossie Panozzo was enrolled into Unley Primary which I also attended. The long daily walk along Mitchell Street, across King William Street and up Park Street to Unley Road, with the school a further hundred metres or so on, was something we both did.

As you might imagine, a casual friendship eventually struck up between us – John and Eric were both a year younger than Ossie and I – which steadily grew into the strongest bond of my youth. Ossie being Italian didn’t hurt either, his family also doing a lot of hilarious – to me, at least - yelling and carrying on over dinners.

We didn’t always walk to and from school either, riding our bikes on a regular basis as well. At Unley Primary, it was somewhat prestigious to have your own number in the bike rack. You could ride to the school gates, then walk your bicycle to the long rack and park it with your front tyre in your assigned rack number.

My other best friend of that time was Fortunata Saccoia, another Italian boy who was a character in his own right. My father was convinced his name was Fortunato, not Fortunata, because Italian names ending in “a” usually are girl’s names and those ending in “o” are boys. For example, Maria or Mario, Antonia or Antonio, Angela or Angelo.

All I know is when I recruited Fortunata to play basketball for Budapest in under-12 boys and we additionally started the halfcourt comp in the back yard, he wrote his own name down and I just copied it. He never corrected it in the weekly program so I can only presume my dad had that one wrong.

The funny thing about Fortunata was he lived across the road in Wattle Street from not only Unley Primary School but its actual front gates. Oddly he was almost always late to school. That is, of course, until he received a bike for Christmas. It was a beaut too, with high handle-bars copying the style of the motorbikes from the Easy Rider movie popular at the time.

Forch, as we abbreviated his name, felt left out, not having a bike rack number so he applied for one. The teachers were in shock at his request, given he lived across the street. But he insisted he would be coming to school by bike so he finally was allocated a rack number.

Ossie and I already were at school, leaning on the fence staring at his house as we watched Forch walk his bike out of the family’s garage at the end of their driveway. He then mounted it, had enormous difficulty getting those high handle-bars under control while also balancing his school bag in his right hand.

Forch then rode up his family driveway next to their house, reached his front fence and dismounted at the gate. He walked the bike down the footpath to the road, looked both ways and walked it across and over to us. Greeting us cheerily, he took the bike through the school gates and walked it to his allocated rack number, parking it there with great satisfaction.

Ossie and I remained amazed he went to the trouble of securing his own school rack number so that, effectively, he could ride along his family driveway. We often asked him why he didn’t just ride up the driveway, then back down and walk across the road as he used to, and he would stare back at us as if we were the crazy ones.

Yep, a character who even his sisters Connie and Lucy found baffling at times. But if there was a loud, raucous and passionate dinner to be had, this was yet another family that was right into it.

THANKS FOR THE VISIT: I hope to have the book "A Type of Life - Memories of an ethnic kid en route to basketball infamy" out in time for Christmas. I'll keep you posted but I won't be posting any more of it!

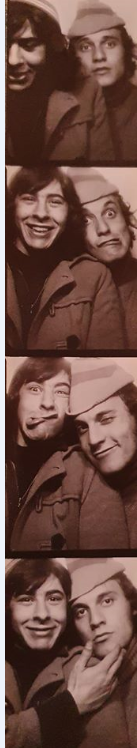

THAT photo booth pic, by the way, is of Fortunata and Oswald, taken at the Royal Show.